Musings on late antiquity and the early Middle Ages | Poems, Crafts, and Food

Monday, 28 December 2020

What I Read and Watched In 2020

Wednesday, 23 December 2020

Piecrust Matters: Taste-Testing the Mince Pies of Lincoln

Season's greetings and I hope you and your loved ones are healthy and safe.

Like many people around the world, the Christmas of 2020 is the first one I will be spending entirely on my own. I've know this was coming since November, but still only managed to make myself pick up the phone and move my flight home less than twenty-four hours before it was due to depart. I've been coping in various ways: reading lots of romance novels, sleeping poorly, going for a run every day, and eating baked goods.

Sunday, 13 December 2020

Is there a doctor in the house?

This week I received two Christmas cards addressed to 'Miss Violist' and there's a furor in the news again about women with PhDs using the title Dr, leading to much reflection on the issue of titles for women here on the barbaricum.

To be clear from the outset, the barbarians hold the position that it is both proper and polite to call someone what they want to be called, without arguing with them about it. This goes equally for names, pronouns, and titles.

"Hello My Name Is Inigo Montoya" by oxygeon is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

"Hello My Name Is Inigo Montoya" by oxygeon is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

If

I am writing to

someone and am not sure what their preference is, I

will typically address the message to 'Dear First Name Last Name' to avoid irritating them by using the wrong title. If I

can see an email signature or a staff profile, I will use the title

indicated there. In a first email to someone I have not met who I know

has a PhD, I will always address them as 'Dr Last Name', or 'Dear First

Name (if I may)'--my intention is to express respect on 'meeting' them for the first time, and invite them to tell me what they

would like to be called. If their reply is signed First Name Last Name,

with an email signature that contains a title, I use that title and

their surname until I either receive a message signed only by their

first name, or I am explicitly invited to call them by their first name.

In sum, Dr Jill Biden introduces herself as Dr Biden? We call her Dr Biden. The barbarians have spoken.

Personally, I deeply dislike the title 'Miss', and will never use it for a woman unless I know that she prefers it. Why should a woman be introduced, before you even know her name, by the fact that she is not married? Oddly enough, I don't have the same aversion to 'Mrs'; in part because of the delightful essay Anne Fadiman wrote about her first awkward encounters with the title Ms, which she eventually came to prefer. One of the small bonuses of having a PhD that no one told me about beforehand was the ability to sidestep the Miss/Ms/Mrs question entirely--'Are you a Miss or a Mrs?' can be answered 'It's Dr, please.'

Why do titles matter? As has been pointed out many times, women are typically addressed by their professional titles much less often than men are, and a lot of the pushback women who insist on 'Dr' get is linked to the dismissal of expertise this implies. One of the best pieces on the question I found pointed out that only a tiny number of the general population (of the US, anyway) actually have PhDs; most people don't fully understand what a PhD means or involves. As Dr Nichole Margarita Garcia point out, using one's title provides an opportunity to share knowledge about what a PhD is with others. Like Dr Garcia, I want to share my PhD with others, and so I prefer to use the title 'Dr' where I can.

Sunday, 6 December 2020

Mile 23

In late October, Shelley Oppel Wood published an essay in Runners' World called 'Stop Calling 2020 a Marathon'. As she points out, the more you think about the parallel, the more it breaks down:

We’ve all heard 2020—a grueling, endless year—described as a marathon. But that only sounds right if you’ve never run one.

This year has indeed felt like the longest of slogs, an endurance test notable mostly for its many varieties of exhaustion and pain. Pandemic and quarantines. Poisonous politics. Violence and rage. And on the West Coast, where I live in Oregon, real fires that fueled the societal ones. But that’s where the parallels end.

With a real marathon, runners know what we’re signing up for. We have months to get in shape. We can find training plans to follow, or even hire a coach. We are mostly in control of the situation, right up to race day—of the miles we log, the dinner we eat the night before, the number of gels we cram in our pockets at the start line.Unlike a real marathon, we weren’t ready in the slightest for what 2020 has brought.

For me, as someone who has run two marathons and was most of the way through training for a third before it was called off due to Covid, the most apt comparison is not the marathon itself, but to a very specific part of it.

Mile 23.

A marathon is 26.2 miles long, and for a slightly-above-average runner like me, the longest run you ever do in training is about 20 miles. Why? A marathon is hard, physically and mentally, and while you do a structured programme of runs to prepare to do it, you arrive on the start knowing that will be the first time you will try to run the full 26.2 miles.

I felt great for the first sixteen miles my first 26.2-miler, the 2018 Yorkshire Marathon. I was doing it! I was running a marathon! And then the rain got into its stride and I realised I had ten more miles to go, and by the time I hit mile 20, I was simultaneously bored and sore and incredulous--I had to keep going for 6 more miles? For real? (A note on being bored: the Yorkshire marathon course is mostly out in the countryside around York--you hit the Minster and the amazing high-fiving vicar within the first 5-10k, and then you are just plodding down flat country roads in rural Yorkshire. Which would be beautiful on a sunny day, but is less so in the rain.) By the time I got to Mile 23, I had reached a state of fatalism: I would be running down Yorkshire roads in the rain for the rest of time, and that was that.

Eventually, mile 23 turned into mile 24, and then seeing the mile 25

sign and hearing people start to yell about the nearness of the finish

line, I rediscovered some spring to my step, and realised that this was

going to end. I was going to make it. I finished in a time of 4:50:19.

|

| The sun came out in the evening, long after the race was over. The nerve! |

My second marathon, Manchester 2019, was a bit different. For one thing, Manchester is a big-city marathon (about 16,000 runners versus the around 5,000 who run Yorkshire), and a substantial portion of the course runs through various boroughs of the city. For another, I started doing speedwork in my training, which helped me get faster and stronger. And finally, I knew that Mile 23 was coming.

And yet. Mile 23 still felt like it was in the middle of nowhere--physically, emotionally, geographically--and also like it was never going to end. A welcome note of absurdity in the endlessness of Mile 23 came when I passed a guy wearing a white rhino costume.

And despite my firm belief that I would be running down the back roads of Manchester for ever and ever, Mile 23 did give way to Mile 24, and then Mile 25. If there was a Mile 25 sign, I missed it, which did have a moment of sending me back to endless-running-land; the race organisers chose to replace it with an enormous television screen showing runners finishing the race, which felt like it was taunting me. But then I looked down at my watch and realised that I had a chance of beating what I thought was my sister's best marathon time, 4:19, and legged it to the finish line, for a 4:18:38 marathon.

|

| Finished! |

As I've had friends celebrate the tremendous good news of promising vaccines, the end of the second UK lockdown, and even the possibility of a return to normal life, I've been alternately bored and sore and incredulous. We're at Mile 23, I shriek silently, we'll be running this thing forever. And for some people--those affected by unemployment, by domestic and racialized violence, by long Covid, by grief and loss--2020 has no end.

Unlike a marathon, those of us lucky enough to be still on our feet did not train for 2020, but I know I am not alone at Mile 23. May we all reach Mile 24, and Mile 25, and sprint towards the finish line as it comes into view.

Sunday, 29 November 2020

Stuffed Pumpkin for Thanksgiving

For my first Thanksgiving in England, I took over a friend's kitchen in Cambridge and cooked a meal for eleven. A few of the guests were vegetarian, so I made two main dishes: a stuffed pumpkin and a turkey. I've made this several times for gatherings over the years--something about a pumpkin stuffed with bacon and bread and cheese seems to please everyone who eats it. Thanksgiving 2020 marks the first time in nearly a decade where I haven't held a Thanksgiving dinner party, so posting one of my favourite dishes to make for others feels like a good way to celebrate.

|

| Looking forward to serving this to friends again when it's safe to do so. |

Pumpkin Stuffed With Everything Good

From Dorie Greenspan's Around my French Table, published in the Providence Journal on October 20, 2010

- 1 pumpkin, between 2.5 and 3 pounds (about 1 kilo). I have used larger and smaller pumpkins depending on what was available in the market, just adjust the amount of filling to the size of the squash.

- salt and black pepper

- 1/4 pound (about 114 g) stale bread, cut into 1/2 inch cubes. If your bread isn't stale, toast the slices in the toaster before cubing them. Any kind of bread you would use for toast will do. I like using a whole wheat (wholemeal) or seeded bread for its taste and texture

- 1/4 pound (about 114g) cheese--something strong and firm, like Gruyere, Emmenthal, Cheddar, or a combination, cut into 1/2 inch cubes

- 2-4 gloves of garlic, coarsely chopped. If your garlic is old or you are sensitive to the taste, you may want to bash the cloves with the flat of a knife and remove the 'germ', which is the green or white bit at the centre of the clove (i.e. the green tip that starts growing when your old garlic starts sprouting). This makes the flavour less harsh.

- 4 slices of bacon (preferably streaky bacon or another kind with a decent amount of fat), cooked until crisp and then chopped. If you are feeding vegetarians, the recipe is still delicious without it,

- about 1/4 cup (about 33g) snipped fresh chives or sliced scallions (spring onions). When I don't have either of these around, I use half a small onion, sauteed until translucent in the fat from frying the bacon.

- 1 tsp dried thyme, or about 1 tbsp fresh thyme

- about 1/3 cup (79ml) heavy cream (double or single cream, it doesn't matter. I once tried to substitute whole milk and it was fine, but cream is much better)

- a pinch of fresh-grated nutmeg. f you don't have a nutmeg grater, you will want a very scant 1/4 tsp of pre-grated nutmeg

Preheat your oven to 350 degrees Fahrenheit (about 176 degrees Celsius). If you have a pot or pie pan that's a bit wider than your pumpkin, grab that, otherwise use a baking tray.

Carefully cut the top off the pumpkin using a sharp knife, just as you would when carving a Halloween jack-o'-lantern. You want a hole that's big enough for you to scrape out the seeds and stringy bits from inside the pumpkin, and off of the top. If you like toasted pumpkin seeds, set the seeds and pulp aside to deal with while the pumpkin is baking.

Make sure to salt and pepper the inside of the pumpkin generously--if you're using a salt of pepper mill, most of the seasoning will fall to the bottom, so you want to get your hands in there and spread the seasoning up on the sides of the pumpkin too. I once skipped this step and regretted it, so make sure you do it--pumpkins, like potatoes, taste good with lots of salt and pepper.

Mix your garlic, bacon, bread, cheese, thyme, and nutmeg in a big bowl. Add pepper to taste. The bacon and cheese may give you enough salt, but taste the filling to see if it's to your liking. Mix in the cream--you don't want the filling completely soggy, since the pumpkin exudes liquid as it cooks, but you don't want it too dry either. It's a bit like stuffing a turkey--a clump of filling should stick together when you pick it up and lightly squeeze it in your hand. Stuff the filling inside the pumpkin.

The precise amounts of bread and cheese and cream you need will depend on the size of your pumpkin. You want to be able to get the lid back on but the pumpkin should be quite full. If you need more filling, just toast and chop some more bread (or just chop it if it's stale), cube a bit more cheese, and add it, with some dribbles of cream, until your pumpkin is filled.

Put the cap on and bake the pumpkin for somewhere between 90 minutes and two hours, or until the filling is bubbling and it's easy to poke a dinner knife into the side of the pumpkin. I usually check the pumpkin and rotate it (my oven has a hot spot) after about the first 45 minutes to an hour of cooking.

After 45 minutes to an hour (for a smaller pumpkin) or an hour to an hour and fifteen minutes (for a larger pumpkin), take the top off so the pumpkin juices can bake away and the top of the filling gets a bit browned. If you forgot to set a timer, this is around when you can poke a knife into the pumpkin but there is still some resistance. The skin of the pumpkin may be golden and blistered in a few spots. Bake the pumpkin with the top off for approximately 20-30 minutes, or until done.

The pumpkin is ready when you can easily stick a dinner knife in its side. Carefully carry the pot to the table or transfer it to a serving plate. If you've got it on a baking tray, take care when carrying it--the pumpkin is very hot and may be a bit wobbly. Cut into 2-4 pieces (small pumpkin) or 4-8 pieces (large pumpkin), and enjoy.

Number of servings depends on the size of pumpkin and diners' hunger levels. Dorie Greenspan says it serves 2-4. I've found that a large pumpkin can serve at least eight, especially if there are other dishes on the table.

Toasted Pumpkin Seeds

Pumpkin seeds are edible and tasty. I like to separate them from the pulp under running water--don't worry about getting them 100% clean, but it helps to remove some of the pumpkin goop.

Put your pumpkin seeds in a pot and cover with several inches of water. Add LOTS of salt (seriously, if you have a good number of seeds from a large pumpkin, you can use a whole tablespoon) and bring to a boil. Or boil the water in your kettle and pour it over the seeds and salt.

Boil the seeds for about 20 minutes or so. I have done as few as 15 minutes and sometimes over thirty, the timing doesn't have to be exact. Pour off all of the water and spread the seeds out on a baking sheet.

You can blot the seeds with a paper towel so they're mostly dry but I don't always bother. Pour over a few teaspoons of oil (you want the seeds to be coated but not swimming) and season to taste. I typically use a little salt (you don't need much after boiling them in salt water), pepper, and about 1/2 tsp paprika or chili powder.

Bake the seeds in the oven with the pumpkin. Check them, and give them a little stir, every 10-15 minutes. It can take them about half an hour to bake--they are done when they look dry and are golden.

Enjoy a nice snack while you're waiting for your pumpkin to finish baking.

Finding a Pumpkin in the UK

Unlike in the United States, there doesn't seem to be much of a distinction between jack-o'-lantern pumpkins (said to be stringy and tasteless) and varieties of pumpkin grown for eating. I have made this recipe with carving pumpkins from a grocery store or vegetable stand and found them to be excellent eating.

Finding pumpkins in the UK can be challenging--they typically start

appearing a few weeks before Halloween and then vanish from stores on 1 November. I get around this by buying my first pumpkin as soon as I see them in stores, and then buying a second (or third) one right before Halloween. Provided the pumpkin skin is free from nicks or soft spots, I've been able to keep them in the kitchen for cooking for at least a week or two--and sometimes as long as a month.

I have found that this recipe also works well with a crown prince squash (which is shaped like a pumpkin and has a light green skin). Actually, I've had good results with any pumpkin shaped squash--just make sure to choose one you can safely carve a lid in.

|

| Both of these pumpkins were used to make stuffed pumpkin. |

Tuesday, 24 November 2020

The White Gloves Problem

So you're sitting on the couch watching television with your resident medievalist, and you get to a scene with a rare book or manuscript. We're watching 'Map of the Seven Knights', an episode from the TV show Grimm, but you could be watching any show or movie. Eyes on the screen, you notice that your medievalist leans forward. They tense.

The characters reach for the rare book or manuscript.

'No, no!' cries the expert on screen. 'You must wear these!'

"White Glove Tour" by Minneapolis Institute of Art is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

"White Glove Tour" by Minneapolis Institute of Art is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The on screen rare book expert hastily dons white gloves and hands the intrepid investigators their own pairs to put on.

|

| A scene from the show Grimm, which inspired this post |

Meanwhile something terrible seems to be happening to your medievalist. Is that...is that high pitched wail coming from them? What on earth is wrong?

Congratulations, friend! You've just met the white gloves problem.

What Went Wrong?

If your medievalist has done an MA (at some institutions, this may also be a part of undergraduate training, but not everyone has this opportunity), they have likely had at least a year's worth of training in how to work with medieval manuscripts--classes both on paleography (the study of medieval handwriting) and codicology (the study of how books are made). If they have gone on to do a PhD, or a second masters' in archival science or rare books librarianship, they will have continued this training. Depending on their field of research, they may even be an expert in manuscripts produced in a particular place or time, or manuscripts of particular genre of writing, such as legal texts.

They probably have never worn white gloves to handle those manuscripts. More than likely, they have been trained not to wear gloves (and if they are a manuscript scholar, they likely don't wear nail varnish much if ever--the manuscripts don't like it, and your medievalist can't handle them with painted nails).

A quick google search reveals that almost every major library has tackled this at some point--as the British Library points out, their experts regularly get scolded by the public for not wearing gloves in videos or photos of them handling their old books! The National Trust explains why wearing gloves to handle rare books and manuscripts actually endangers them. The Smithsonian's essay on the subject stands in solidarity with your whimpering medievalist.

Have you ever tried to text someone wearing your winter gloves? You keep stabbing at the keypad on your screen, and hitting all the wrong letters, and it takes forever to hit the right ones. That same lack of dexterity applies to handling ancient pages with gloved hands: you have less dexterity and control over your touch. You might accidentally tear a page or swipe your finger across a flaking bit of ink. Plus, cotton gloves are not perfectly smooth--fibres from the glove might snag on the material you're handling. Anyone who's ever been around a little kid knows that white fabric stays white for...typically not long, meaning that those pristine white gloves are likely to be picking up dirt and spreading it on the book, not keeping it off. Counter-intuitive as it may seem, your bare hands (freshly washed and dried and free of lotion or nail varnish) are safer for the book.

This is not news--librarians and archivists and medievalists and other specialists in old stuff have been counteracting the white gloves problem for a long time. So why do the white gloves persist?

Strategies of Distinction

|

| Don't do this. |

Sunday, 15 November 2020

#Keepshowingup: My CV of Failures

About four years ago, the idea of the 'CV of Failures' made the rounds of academia-centered social media and higher education periodicals. By listing unsuccessful applications, successful scholars such as Johannes Hauerhofer aimed to give perspective on their careers and achievements, and normalise discussions of academic rejection. Hauerhofer's full CV of Failures can be found here, and he provides links to other scholars' CVs of Failures as well.

Monday, 9 November 2020

Mittens and Madame Vice President

It's been a long week and I don't have an eloquent post in me so here is a list and mittens.

1. Kamala Harris is now vice president-elect of the United States.

2. She will be the first woman, and the first woman of colour, ever to hold this office.

3. As someone who got into history through reading and writing about American women's history for school projects, I was moved to tears when I heard Kamala Harris say that she will be the first woman to hold this office, but not the last.

4. 'Dream with ambition' is a wonderful message for children. And the rest of us, too.

5. I have spent the past day and a half watching every video I could find of the joyous cheering and honking of car horns that took place across America when the election was called for Biden and Harris.

6. One of my favourite one-liners about the election result is

So, the guy with the stutter beat the bully.

— Hank Green (@hankgreen) November 8, 2020

7. Another favourite one-liner occurred after I texted some friends from work, 'So how many people do you think tweeted at Trump that he's fired tonight?' and one of them immediately replied '74 million'.

8. The first presidential election I voted in was in 2008, and I remember watching the results come in with members of my college fraternity. Someone shouted 'It feels like we just blew up the Death Star!' when the election was called for Obama.

9. This week I want to make donations to food banks and get out the vote organisations, such as Fair Fight, in Georgia. I am in awe of Stacey Abrams and the many other organisers whose work made the difference there.

10. Today I reknit the thumbs on a pair of mittens to be the appropriate length. They would have been finished before this, but I sat on them for several weeks trying to convince myself that a too-short thumb was something I could cope with.

|

| Faux cable knitted mittens |

11. The yarn comes from Caithness Yarns, whose proprietor won my heart by repeatedly referring to his "sheepies" when we spoke at a wool festival.

Sunday, 1 November 2020

My Favourite Poem

One Art

of lost door keys, the hour badly spent.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

Then practice losing farther, losing faster:

places, and names, and where it was you meant

to travel. None of these will bring disaster.

I lost my mother's watch. And look! my last, or

next-to-last, of three loved houses went.

The art of losing isn't hard to master.

I lost two cities, lovely ones. And, vaster,

some realms I owned, two rivers, a continent.

I miss them, but it wasn't a disaster.

-Even losing you (the joking voice, a gesture

I love) I shan't have lied. It's evident

the art of losing's not too hard to master

though it may look like (Write it!) like disaster.

In trying to remember where I discovered this poem, I think first of the Writer's Almanac. This was a short radio segment in which the American radio personality Garrison Keillor read a short poem and offered a brief overview 'on this day in history' centered on writers and literature. Keillor was accused of sexually harassing female coworkers 2017, and his shows disappeared from public radio. Further digging reveals that the Writer's Almanac featured numerous poems of Bishop's over the years, but never 'One Art', so I don't actually know where I first found it. High school, browsing one of the English classroom's Norton Anthologies, having finished my class reading? At university, somehow? I am not sure. It is a poem so much a part of me that I cannot remember when I did not know it. It has spoken to me at many different times in my life. As the UK enters its second lockdown, it seems worth revisiting once more.

Sunday, 25 October 2020

A Use for Fennel and Other Successful Kitchen Experiments

This blog is called the barbarians are hungry for a reason: I love to eat! Here are some new recipes I have tried over the past few months.

August

- Aloo Gobi from Masala

- Fennel and Pork Stir Fry from Chicken and Rice

- Gavurdagi Salatasi from Persiana

- No-Churn Rhubarb Condensed Milk Ice Cream from Chicken and Rice

- Banana Pancakes from Good and Cheap

To keep things interesting: in August, I took a lot of walks, and on one of these I met Bert. Must check what Bert is up to for Hallowe'en...

|

September

- Extra-Fancy Egyptian Ful Medames from Home is a Kitchen

|

| In September I saw the North Sea for the very first time. |

October

- Life-Changing Cinnamon Tahini Cookies from Sweet Potato Soul

- Jingha Sukha Pulao from Masala

- Cornmeal Molasses Pancakes from Heartland

- Lamb Raan from Dishoom

- Caucasian BBQ Flatbreads from Mamushka

- Apple Oatmeal Cookies from The Hummingbird Bakery Cake Days

- Apple and Currant Oatmeal Bars from The Hummingbird Bakery Cake Days

- Potato and Leek Pizza from Good and Cheap

|

| Discovered a statue for our times in a park in my neighbourhood. Eeek indeed! |

Fennel & Minced Pork (Pad Ka Prao)

- 1 small fennel bulb (I use both the bulb and the fronds, if they're attached)

- 2 tbsp oil

- 4 cloves garlic, chopped

- 200g minced pork (aka ground pork, 200g is roughly a cup and a half)

- 1/4 tsp chili flakes, or a 1-inch square block of chopped frozen chilies from the freezer (I've never made this with fresh chilies, but suggest you go by your own spice tolerance in deciding how much to add)

- 1 tbsp fish sauce

- 1 generous tsp oyster sauce

- a generous pinch of brown sugar (it's fine without it)

- a big bunch of basil leaves (this is supposed to be Thai basil, but I use the only kind I can find in our grocery stores, regular old Italian basil, and it tastes good. You could also try fresh coriander/cilantro.)

- an egg per person (optional)

To make:

- Put rice on to cook--I typically boil my rice, using a 3-to-1 ratio of water to rice grains. For a meal and leftovers, I typically use a cup of rice and 3 cups of water.

- Wash your fennel and chop it into bite-sized pieces. I usually chop off the fronds, set them aside, chop the bulb, and then add the chopped fronds after the bigger and thicker pieces have cooked a bit.

- Heat your oil in a frying pan and add the chopped fennel bulb. Add chopped garlic, and fennel fronds if you have them. Stir-fry until it all smells nice, just a few minutes. If using frozen chopped chili, add it here.

- Add in the ground pork, using a spoon or spatula to break it into much smaller pieces.

- When the meat is just abut cooked, add in chili flakes (if using); then add fish sauce, oyster sauce, and sugar. Add about 1/8 to 1/4 cup of water, which helps make a nice sauce.

- Remove frying pan from heat and add in basil leaves. Mix them in until the residual heat from cooking causes them to wilt.

- If you are using ordinary white rice, and started cooking it before chopping your fennel, it should now be finished cooking. Dollop some on a plate and top with stir fry. Fry egg(s) in the pan, and top each plate with a fried egg.

Sunday, 18 October 2020

What are wantos? An investigation of medieval mittens

Here in the flatlands of England, it's been hovering around 10-12 degrees (the low fifties Fahrenheit) for the past few weeks--just a little bit colder and I'll be wearing mittens every time I leave the house. This week I'm trying to finish a review of Ian Wood and Alexander O'Hara's translation of Jonas of Bobbio's Life of Columbanus. Columbanus was a cantankerous seventh century Irish saint who spent his life founding monasteries, standing up to royalty, and deploring the state of Christian observance in Gaul (where he moved permanently early in his career). In this post, I want to leave Jonas' colourful and opinionated account aside, and focus on a question of true interest: is this the first medieval Latin text to mention mittens?

Our evidence from Jonas is the following:

Another time when he (the blessed Columbanus) had come to eat at the aforesaid monastery of Luxeuil, he laid his gloves, which the Gauls call wantos, and which he was accustomed to wear when working, on a stone which was outside the door of the refectory. As soon as it became quiet, a raven, a thievish bird, flew up and snatched away one of the gloves in its beak. After the meal, the man of God went outside to get his gloves. When everyone was wondering among themselves who could have take [the glove], the holy man declared that no one would dare touch it without his permission except that bird which was sent out by Noah and did not return to the ark. And he added that the raven would not be able to feed its young if it did not quickly restore what had been rapaciously stolen. Then, while everyone was waiting, the raven flies into their midst bringing back what it had stolen in its wicked beak. And it does not attempt to fly away again, but humbly in the sight of all and forgetful of its wild nature awaits punishment. The holy man instead orders it to depart. [Wood and O'Hara, Life of Columbanus, pp 126-7]

|

| The thief! "Raven" by Sergey Yeliseev is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 |

As Wood and O'Hara note in the footnote, the term they translate as gloves is literally tegumenta manuum ('covering for the hands'); they say that the local word, wantos, 'becomes the modern French 'gants'' and that Jonas remarking on this different shows 'that he was writing from an Italian perspective' (p 126 n 186). Jonas was a monk from the northern Italian town of Susa, acquiring the sobriquet of Bobbio as that was the monastery where he entered religious life, and later in his career he spent some time working as a missionary on the northeastern borders of the Frankish kingdom--so from his perspective Frankish vocabulary was new and interesting, and worth defining for someone who might not know it.

What exactly is he describing here? What are wantos?

Firstly, despite my initial excitement about mittens (I had just started knitting a pair when this passage caught my eye), Jonas probably isn't describing knitted mittens. There are two reasons for this. Firstly, Jonas never describes the specifics of the hand coverings. Clearly, it was something durable: the chapter this miracle is included in contains two other miracles, all of them concerned in some way with outdoor work: one of which involves the miraculous healing of someone who accidentally cut off his finger with a very sharp sickle, the second a man who was healed after being struck in the forehead by a bit of debris while splitting wood; and then finally the miracle we're concerned with, where the type of work isn't specified, but the fact that Columbanus left his tegumenta manuum on a stone outside suggests muck of some kind was involved.

Secondly, if the mitten was made of yarn, it likely wasn't knitted. As far as can be seen from archaeological discoveries of Viking-era and early medieval textiles, the most popular technique for making fabric out of sticks and string was naalbinding (or nålebinding), which uses a thick needle with a large eye and short lengths of yarn to form a knit-like fabric through looped needle netting. Below is an example dating from sometime between the tenth and the twelfth century.

|

| "Medieval mitten, National Museum of Iceland" by Lebatihem is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2. |

Jonas was writing in about 640--can we find a mitten closer to that date? The answer is yes--a woolen mitten dated from between 600 and 800 survives from Aalsum, in the Netherlands; and a mitten discovered at Dorestad, an important early medieval port near Utrecht, dating from between the seventh and the ninth centuries, was evidently deliberately felted to make it warmer and impermeable to wet and weather.

| |

Mitten from Aalsum (Fries Museum, object nr. FM 33-374). Picture from the Twitter feed of the archaeologist Annemarieke Willemsen, who has written extensively about medieval gloves and hand-coverings. |

|

Mitten found in Dorestad (National Museum of Antiquities Leiden, object nr. WD375.3.1) |

It's difficult to tell, but it looks almost like the Dorestad mitten has a top flap which might fold up over the fingers to allow the wearer greater dexterity. And there is a final consideration too: depending on the work Columbanus was doing, he might have found leather wantos rather than woolen ones a more comfortable and practical choice.

The waterlogged conditions at a sixth or seventh century Alamannic cemetary at Oberflacht, in southwestern Germany, preserved a wide array of wood, textiles, and leather--including, in the Grave 17, a set of leather gloves, described in William Wylie's translation of the 1847 German publication of the excavation,

No 17 contained a couch [wooden coffin]. In it were a singular pair of leather gloves, strongly laced on the back of the hand, and lined inside with a soft cloth, almost perished.

Wylie's article is accompanied by engravings but the gloves are sadly not among them. For a few pictures of what they might have looked like, Tomáš Vlasatý's 'Early Medieval Mittens' rounds up some interesting images (here)

When I went looking for other uses of the word wantos in the Monumenta Germaniae Historica (a freely available collection of editions of late antique and early medieval Latin texts), I discovered that what few mentions of wantos there are also appear to involve stories of them being stolen. The word appears in the Life of St. Philibert of Jumièges, Ch 12, which seems to be from mid-eighth century; and the Martyrology of Wolfhard of Herrieden, Book Three, Ch Four, which dates from c. 895. Both stories involve the miraculous prevention of the theft of gloves. A further reference also gives the sense that wantos were valuable: the Constitutio of Abbot Ansegisus of Fontanelle, (c. 823/833), lists a pound of gloves (ubantos) as one of the items the abbot gave to the monastery.

We began with the question of whether Columbanus' wantos are the first medieval Latin text to mention mittens. The answer to this question is both yes and no. As far as I can tell, this is the first medieval text to use the word wantos--it clearly wasn't a common word, and all other uses seem to be later than c. 640, when Jonas was writing. On the other hand, it's not entirely clear whether wantos is best translated as mitten (or glove), as none of the writers who use the word reveal whether the hand covering has separate fingers. Surviving examples of early medieval hand covering suggest that it didn't, making it likely that Columbanus' wantos was a mitten.

One thing is clear from the unexpected theft and return of Columbanus' mitten (or glove). Like handknitted mittens today, wantos were valued, and it was a miracle indeed to have a missing one restored.

Further Reading

Elizabeth Coatsworth and Gail Owen-Crocker, Clothing the Past: Surviving Garments from Early Medieval to Early Modern Europe (Leiden, 2018)

Ferdinand von Dürrich, and Wolfgang Menzel, Die Heidengräber am Lupfen (bei Oberflacht) (Stuttgart, 1847). Available from http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10003615-7.

'Gloves and Mittens from the Past', Medieval Histories (12 January 2016) Available from https://www.medieval.eu/gloves-and-mittens-from-the-past/ [accessed 18 October 2020]

Satu Novi, 'Viking and Medieval Nålebinding Mitten Replicas', Katajahovi (2017). Available from http://www.katajahovi.org/en/viking-and-medieval-nalebinding-mitten-replicas.html [accessed 18 October 2020]

Tomáš Vlasatý, 'Early Medieval Mittens', Projektu Forlǫg (19 January 2019) Available from https://sagy.vikingove.cz/early-medieval-mittens-and-gloves/ [accessed 18 October 2020]

Annemarieke Willemsen, 'The Geoff Egan Memorial Lecture 2013: Taking up the glove: finds, uses and meanings of gloves, mittens and gauntlets in western Europe, c. AD 1300–1700' Post-Medieval Archaeology 49:1 (2015), 1-36.

Ian Wood and Alexander O'Hara, Jonas of Bobbio: Life of Columbanus, Life of John of Reome, and Life of Vedast (Liverpool, 2017)

William Wylie, 'The Graves of the Alemanni at Oberflacht in Suabi' Archaeologia 36, (1855), pp. 129-168. (If you are interested in reading more about the Oberflacht gloves, I wasn't able to find a copy online, but Siegwalt Schiek's 1992 thesis Das Gräberfeld der Merowingerzeit bei Oberflacht looks like the best place to start).

For addutional roundups of archaeological discoveries, survivals, or depictions of medieval gloves and mittens, see the roundup at Medieval and Renaissance Material Culture (here); a shorter list can be found at The Viking Age Compendium by Gavin and Louise Archer (here)

And finally, because they're too amazing not to share, here is a pair of late medieval knitted gloves, made for a bishop in Spain.

Sunday, 11 October 2020

The Value of Learning Latin from Medieval Authors

Sayers delivered the speech 'Ignorance and Dissatisfaction' at the 1952 Summer School of the Association for the Reform of Latin Teaching; it can be found in various places on the internet now, but few people who post it acknowledge that Sayers was confessing her ignorance of Latin to an audience of Latin teachers, not the easiest crowd in front of whom to admit mistakes, then or now.

|

| Dorothy L. Sayers, with friend, in Witham, Essex |

Sayers began learning Latin at six years old, taught by her clergyman father, who had previously been a Latin teacher to the small boys ('small demons with angel-voices') at the school of Oxford Cathedral. Sayers' recapitulation of her childhood reactions to moving from memorising the declension of nouns and the conjugation of verbs into more advanced features of the language, is worth enjoying in full:

...the Active Voice, always friendly, except for a tendency to confusion between the Future Indicative and Present Subjunctive of the Third and Fourth Conjugations (the rot always seemed to set in at the Third Anything); the Passive Voice always lumbering and hostile ; the Deponents lurking meanly about, hoping to delude one into construing them as Passives; verbs like fero, so triumphantly irregular as to be permanently unforgettable ; verbs with reduplicated perfects of a giggling absurdity — peperi was always good for a hearty Victorian —and defectives, which were simply a mess. It is a nostalgic memory that I could at one time recite the whole table of irregulars without more than an occasional side-slip ; and I still remember at utor, fruor, vescor, fungor are followed by the ablative, when any more generally useful fragments of knowledge have slipped to Lethe and vanished.By this time, of, course, the girls, the poets and the roses had upped into the background. We marched with Caesar, built walls with Balbo, and admired the conduct of Cornelia, who brought up her children diligently in order that they might be good citizens. The mighty forest of syntax opened up its glades to exploration, adorned with its three monumental trees—the sturdy Accusative and Infinitive, the graceful Ablative Absolute, and the banyan-like and proliferating Ut and the Subjunctive. Beneath their roots lurked a horrid scrubby tangle of words beginning with u, q and n, and a nasty rabbit-warren of prepositions. There was also a horrid region, beset with pitfalls and man-traps, called Oratio Obliqua, into which one never entered without a shudder, and where, starting off from a simple Accusative and Infinitive, one tripped over sprawling dependent clauses and bogged one’s self down in the consecution of tenses, till one fell over a steep precipice into a Pluperfect Subjunctive, and was seen no more.

As a young woman from a solidly middle class Victorian clerical family, Sayers had a governess and studied other languages as a child and teenager--German and French. She recounts that her growing fluency in reading and speaking these languages led her to prefer them.

To do a degree at Oxford in Modern Languages (women were only officially granted Oxford degrees from 1920 onwards, so Sayers' 1915 degree was awarded retrospectively), students of the first world war era were required to pass examinations in Greek and Latin. Sayers recounts managing to scrape through these experiences, and then starting to forget large pieces of the language in being preoccupied with other things. At the same time, though, her participation in choirs which sang medieval music left her with an awareness of

the shimmering, spell-binding magic of the mediaeval Latin

After twenty years of learning Latin, Sayers writers, she was left uncertain how to pronounce the language (having been taught multiple versions), unable to compose her own Latin prose or verse, and unable to comfortably read Latin, let alone distinguish the characteristics of different authors. And yet, she robustly defends the usefulness of Latin, for four main reasons:

- Latin Grammar teaches its students how languages work: they are consequently better able to write clearly, since English grammar is far from intuitive

- Something like half of English vocabulary has Latin roots, so someone who knows Latin has access to a wider and richer vocabulary

- Knowing Latin makes learning other Romance languages, or indeed any inflected language (that is, a language where grammatical meaning is conveyed by varying the endings of words) vastly easier; or as Sayers puts it: 'Why should a child waste time learning half-a-dozen languages from scratch, when Latin would enable him to learn them all in a fraction of the time?'

- It helps the reader make sense of allusions and Latin phrases she encounters in reading older European and English literature. (Or indeed, for the modern students, the formulas of exorcism on Supernatural, spells in the Harry Potter books, or memorial plaques in churches or public buildings...)

Sayers concludes her speech with a series of recommendations for teaching Latin in such a way as to avoid her own difficulties with the language.

Of these, the least useful is her ironclad insistence that students must begin Latin at the age of six or seven, an age where she claims they are interested in the work of memorisation that is the backbone of fluency in reading. I didn't start learning Latin until just after I turned twenty; most of my students have been at least this age if not older. While scientific research on language acquisition has only gotten clearer since Sayers' day--it is easier, faster, and of longer-term benefit to acquire multiple languages as a child--the arrow of time flies only one way.

Her suggestions for pronunciation, since this was her own insurmountable hurdle to the language, are helpful. In particular, she points to the fact that anyone who speaks a Romance language is likely to be guided in their pronunciation by the conventions of this language, and it gives the speaker something familiar to hold on to. Sayers discusses some of the practical difficulties (not very many) of English pronunciation for beginners, and suggests that the use of ecclesiastical pronunciation is the way forward.

In my own teaching, I typically default to pronouncing Latin as though it were Italian, since this is the first foreign language I learned; occasionally I am influenced by Latin I've heard sung in churches. Some of the vowels are undoubtedly wrong, but it at least means I am saying each letter or syllable that I see on the page, which I personally find helpful. I find French a bloody nightmare to read or speak, since I can never keep straight which letters I'm supposed to say and which I'm supposed to swallow, never-mind what those letters should actually sound like...! Because pronunciation can be a sticking point for some people, I encourage my students not to worry too much about saying things 'wrong'; the important thing is to get them out aloud, and then we have something to work with. As Sayers advises, consistency is the main thing to avoid confusion.

Sayers is on to something with her recommendation that students start their Latin with texts that they can read comfortably--avoiding an immediate dive into Virgil or Ovid or other authors from the time of the emperor Augustus. Firstly, these authors are way too hard, and second of all, they are far removed, culturally, from anything with which students can reasonably be expected to be familiar. Sayers' suggestion, instead, is that the rich field of medieval Latin--over fifteen hundred years of literature, mind--is a sensible starting point. For one thing, it's closer to modern languages in sentence structure and construction, and particularly for adult learners, it simply makes more sense to start with the modern form of a language and then work one's way back to its ancient versions.

Sayers advocates for speaking and writing Latin as a way to learn it. As someone who is abysmally bad at crossword puzzles and could be beaten by a dog at Scrabble, this is the sort of mental gymnastics my brain flails at. But I was made to do it as an undergraduate, and make my students do it anyway--for one thing, it humanises the language, and for another thing, it is the best way I know to make one's understanding of grammar and vocabulary absolutely ironclad. Someone can come up with the correct Latin-to-English translation without really understanding what they're doing; it simply isn't possible to do the reverse. Plus, the sense of achievement it gives is unparalleled.

|

| A side benefit of learning Latin is that once you know it, you start to see it everywhere |

For students of Sayers' own generation, and the students of the teachers she was speaking to in 1952, language learning was a routine part of becoming an educated person. One thing I commonly hear from my students (especially British students) is that they just aren't any good at learning languages, as though one either has it the way some musicians have perfect pitch, or one doesn't, and without this gift access is forever denied. (One can see the ancestor of this thought in Sayers' speech, where she describes herself as someone with 'the gift of tongues.')

I don't like this thinking, not least because I consider myself to be in the same boat as those students. I am a native English speaker and can fumble reading or speaking five more: French, German, Italian, Latin, and Old English. And I wish I were better than I am at all of them. My issue is one that I expect actually lies at the root of many other people's insecurities about their linguistic abilities, a la this scene from Pride and Prejudice:

'My fingers,' said Elizabeth, 'do not move over this instrument in the masterly manner which I see so many women's do. They have not the same force or rapidity, and do not produce the same expression. But then I have always supposed it to be my own fault -- because I would not take the trouble of practising. It is not that I do not believe my fingers as capable as any other woman's of superior execution.'

Sayers emphasises this indirectly in her speech, although it is easy to miss since she is primarily talking about the benefits of daily individual tuition with a native speaker (the sort she got from having a French governess)--a key to language-learning is regular practice. One has to persist, even when it's confusing or boring. One of the things I address in my teaching is that a lot of students, especially ones who have never spent much time learning a language, don't know how to revise grammar or vocabulary.

I start by focusing on the value of memorisation. One thing I see with weaker students is that they insist on making sure to copy down 'the correct translation' of a sentence, so they can go away and memorise it for the exam. First of all, that memorisation energy would be much better spend on vocabulary of the sentence, and how the grammar works--this enables them to go away and read other sentences, not just regurgitate the one in front of them. Secondly, the idea that there is One True Translation is rarely if ever accurate--once one gets into translating sentences of any length or complexity, variations of the translation bring out different shades of meaning. And with really tough stuff, like the Life of Columbanus by Jonas of Bobbio or the Cosmographia of Aethicus Ister, that act of interpretation becomes an argument about what the author means and how the text works--which the reader can then take, leave, or challenge according to their own interpretation. Relying on someone else's translation as authoritative is deliberately choosing to see the world in black and white--you miss the richness of shades of colour and meaning.

There are limits to this, and especially for beginners, striking a balance between accuracy (their translation has to accurately reflect the person, number, tense, and mood of the verb or it just isn't right) and flexibility (recognising that Latin words might have several English equivalents) can be a challenge. After all, medieval people spoke and understood Latin, and an overly literal translation turns Latin into a language it's impossible to imagine real people ever speaking or writing, which leads someone already feeling like they're drowning to stop swimming. As Sayers rightly acknowledges, the right choice of reading is a great help--students are more likely to keep doing if what they're having to read is actually interesting.

When I was in high school, I played in the Rhode Island Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, which had occasional visits from an esteemed professional conductor, Larry Rachleff. At one point, when we were all playing something very badly, after repeated attempts to get us to play it right, he stopped us, took a deep breath, and said 'You all think I'm crazy because I care this much. I think you're all crazy because you don't.'

It's a perfect summary of what makes good teaching such a challenge--you have to think what you're doing matters, and you have to inspire other people to go along with it.

I love medieval Latin, in all its strange beauty and contradictions, and I hope that this year I will help at least a few of my students love it too.

Sunday, 4 October 2020

So how's your pandemic going?

The coming week is welcome week at my university, so everything is at sixes and sevens and so am I. Sending every good wish for the physical and mental health of anyone reading this who is also preparing to go back into the classroom or is already there. The UniCovid UK site is both terrifying and helpful reading, and that is all I want to say for now about coronavirus and universities.

Instead, I want to offer a piece of writing that I found helpful. In the May 2020 the Letters Page, one of my favourite periodicals, published a lockdown letter by the Canadian writer Aislinn Hunter. The following paragraphs profoundly spoke to me:

I worry about the usual things: my students, the economy, this awful and unsettling loneliness, the future. But I also worry about the potential for a gulf in understanding to take hold on the far side of this pandemic. It seems almost impossible to imagine what it’s like to wake up to the news that another, and then another, of your neighbours has died, to lose elder after elder in a community, to lose a family member who worked the front lines because that’s what they were trained to do. And I am a writer who spends significant amounts of time in the imagination… I’m someone who recently lost a husband of twenty-five years, though he died in my arms and it was only our world falling apart at the time, not everyone’s.

There’s a feeling you get sometimes walking through a city marked by tragedy – it’s a feeling I had standing in the cathedral in Coventry, in some of the German cities I travelled through last October, in Portbou in Northern Spain where my husband and I spent time after he’d gone though radiation and chemotherapy for his cancer. I worry those who have lost loved ones to Covid – who weren’t able to say good-bye, who live in villages and cities where relations and friends and neighbours were taken in large numbers – will end up standing on the other side of a veil from those who come out of this with a greater remove from the situation. I worry that we won’t be able to meet through language across the two sides of this divide. This is why I think stories and new forms of remembrance will become so important. To witness one event is no small matter but to witness something that sweeps over all of us in an uneven storm will require new forms of empathy; active listening.

Experiences across the pandemic have been so different. Members of senior leadership teams, programme leaders, catering staff, associate demonstrators, trainers at the university gym--even within groups of people who hold the same sort of job, let alone people who work for the same university but have different roles, there has been such an incredible variety of experiences. As the only non-European member of my team, having my entire family an ocean away, and following the coronavirus and other disasters in my home country, has been a different experience from everyone else's. Such differences have at times made me feel extremely alone. As Hunter says, even for someone whose work is literally exercising the imagination, the divide between communities which have been severely affected and communities which haven't is profound.

My own steps to acknowledge this divide have been small ones. Finding myself helplessly enraged whenever I received an email hoping that I had a nice or fun or relaxing summer ('I didn't, but I hope you did' doesn't feel very polite), I have tried to stop beginning emails with 'I hope this finds you well'. In normal times, this seems like an expression of good wishes--in pandemic times, I worry that this assumes the person I am addressing is fine, which is not a burden I want to put on them if they aren't. Instead I try to write things like, 'I hope this finds you and yours well and safe', or 'I hope you are hanging in there', or even 'How are you?' I've moved from closing my emails with 'sincerely' to 'take care'. Another small step that helps me is calling staying apart 'physical distancing' and not 'social distancing'. This reminds me that my social connections are taking some new forms for now, but they are still very much there.

A Sock Update and Other Coping Strategies

Colourful wildflowers growing at a local cemetery |

The sun is setting much earlier now, and I don't know what the next few months are going to be like. (Other than, of course, darker. November through February in the UK is a long dark teatime of the soul even in a good year.) One of the joys of taking regular walks through my neighbourhood has been paying attention to changes in the natural world--every few weeks I walk through a local cemetery to see what their wildflowers are doing lately.

It also helps to knit and watch a lot of science fiction & fantasy television. Which brings me to a cheerful place to end--I figured out my second sock.

|

| Second sock success! |

Somehow, in a pattern which read:

Rounds 1, 3, 5, 6: knit

Rounds 2 & 4: Knit 2, Purl 2

I came up with:

Round 1: knit

Round 2: slip 1, purl 1

Part of what took me so long to work this out is I had utterly no memory of slipping stitches, let alone doing so for the entire leg of a sock.

Take care.

Sunday, 27 September 2020

First Thoughts on Vocational Awe in Academia

Do you ever read 'quit-lit'?

For the past few years, essays written by someone who has left academic employment about why they did so have resonated with me. I work in a university but am not on a research or teaching contract, which sometimes matters not at all and sometimes matters very much. Sometimes I am grateful that my work still allows me access to a number of resources I can use to write history, sometimes I am frustrated that I don't have access to some of the resources, time, and respect I took for granted as a PhD student.

I am one of the lucky ones. A month before submitting my PhD, in September 2016, I moved to my current city because my then-partner got a job here. After a year of putting together part-time jobs as a library assistant, associate lecturer (British for TA) at two universities, short-term early career researcher, part-time research administrator, in September 2017, I was simultaneously offered a permanent job as an academic librarian, and a one-year postdoc researching late antique saints. I chose the permanent job and three years later, with the world gone to hell, I am still here.

For the first year and a half, I didn't appreciate my good fortune. The other side of academic libraries was and is an eye-opening experience, and so too was the response of most academics: oh, they said, are you able to make time for your research and writing during your work day? (As though being a librarian was a job they could not imagine actually taking eight hours a day.) The fact that I have a PhD, and not an MLS/MLIS, was similarly baffling to many librarians. At one of the first library conferences I ever went to, a fellow attendee introduced herself to me by demanding to know where I went to library school. Finding Chris Bourg's blog post on feral librarianship was an immense help with my feelings of being, as the saying goes, neither fish nor fowl.

Plus, I was actively applying for the academic jobs and early career research grants, to the point where that was all the writing I did, outside of preparing conference papers. I had a number of interviews, but none resulted in an academic job. In between a few of the more devastating rejections, I came across Dr Erin Bartram's essay on her experience of leaving academia. I read the following paragraphs and finally found words for something I had been feeling but unable to articulate:

Quit-lit exists to soothe the person leaving, or provide them with an outlet for their sorrow or rage, or to allow them to make an argument about what needs to change. Those left behind, or, as we usually think of them, those who “succeeded”, don’t often write about what it means to lose friends and colleagues. To do so would be to acknowledge not only the magnitude of the loss but also that it was a loss at all. If we don’t see the loss of all of these scholars as an actual loss to the field, let alone as the loss of so many years of people’s lives, is it any wonder I felt I had no right to grieve? Why should I be sad about what has happened when the field itself won’t be?

Even in our supportive responses to those leaving, we don’t want to face what’s being lost, so we try to find ways to tell people it hasn’t all been in vain. One response is to tell the person that this doesn’t mean they’re not a historian, that they can still publish, and that they should. “You can still be part of the conversation!” Some of you may be thinking that right now.

To that I say: “Why should I?”

Being a scholar isn’t my vocation, nor am I curing cancer with my research on 19th century Catholic women. But more importantly, no one is owed my work. People say “But you should still write your book – you just have to.” I know they mean well, but actually, no, I don’t. I don’t owe anyone this book, or any other books, or anything else that’s in my head.

“But your work is so valuable,” people say. “It would be a shame not to find a way to publish it.”

Valuable to whom? To whom would the value of my labor accrue? And not to be too petty, but if it were so valuable, then why wouldn’t anyone pay me a stable living wage to do it?

I don’t say this to knock any of my many colleagues who write and publish off the tenure-track in a variety of ways that they find fulfilling. I just want us to be honest with ourselves about who exactly we’re trying to comfort when we offer people this advice and what we’re actually asking of those people when we offer it.

Dr Bartram goes on to write about the fact that a PhD in History trains those who earn it to be a history professor and nothing else. My own PhD programme only started running events where alumni came and talked about their careers, let alone talks on how to apply for academic jobs, in the last year I studied there--and even the careers events were tailored towards academic work. (Professors' biographies and departmental webpages list former students who have gained academic jobs, but no other alumni.) Even PhDs don't know what else you do with a PhD...

Even with all the stars aligned to keep writing: a stable job, healthcare, good internet, a safe place to live, decent (but not great) access to paywall-protected academic databases and journals, and excellent alumni library access through one of my former universities, I struggled with the question Dr Bartram asks. If producing academic writing is not part of my employment--and there is an excellent piece, here, about the fact that historians don't typically make money for this sort of writing--why do it? If you want to be a writer who specialises in history, you don't need a degree that trains you to be a history professor. Most trade nonfiction about the past is not written by authors with history PhDs; and a doctorate doesn't typically train its recipients to write well.

I moved halfway around the world to become a historian, I didn't earn a PhD so I could write (unpaid) in my spare time. The degree was my entry ticket into the profession, neither a hobby project nor the sum total of my life (shout-out here to everyone who advised, in my first two years of librarianship, that I should spend my evenings and weekends writing in order to maximize my chances of academic employment). When I read Fobazi Ettarh's article on vocational awe in librarianship, it felt like I finally had the words to express some of what I saw and felt about academic work--the emphasis on teaching and research as a calling, the framing of the academic community as a sacred space, the endless job-creep of publishing expectations and student satisfaction, and more.

The fact that I have chosen to resurrect this blog and produce academic and hopefully other kinds of writing, seems to fly in the face of all that I have just written. Quit lit, after all, is about quitting. Being done. Finished.

And yet.

No one is owed my work. I used to find the W.H. Auden quote 'You owe it to us all to get on with what you're good at' a source of inspiration when I was working on job applications. Now, thinking these things through, it grates. No one is owed my work.

I am uneasy with the idea that I am writing for my own fulfillment--once more for the folks at the back, I did my PhD as a professional degree. And I struggle with the idea of my writing as a historian being useful to myself or anyone else, a question the following poem raised for me when I stumbled across it.

To be of use

The people I love the best

jump into work head first

without dallying in the shallows

and swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight.

They seem to become natives of that element,

the black sleek heads of seals

bouncing like half-submerged balls.

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience,

who strain in the mud and the muck to move things forward,

who do what has to be done, again and again.

I want to be with people who submerge

in the task, who go into the fields to harvest

and work in a row and pass the bags along,

who are not parlor generals and field deserters

but move in a common rhythm

when the food must come in or the fire be put out.

The work of the world is common as mud.

Botched, it smears the hands, crumbles to dust.

But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry

and a person for work that is real.

~ Marge Piercy

From Circles on the Water: Selected Poems of Marge Piercy

(Alfred A. Knopf, 1982). Available online at the Poetry Foundation, here

For now, the only answer I have come to is that I owe it to myself to keep writing, and I owe it to others to keep learning, and extend help and welcome however I can.

Sunday, 20 September 2020

Weaving Words

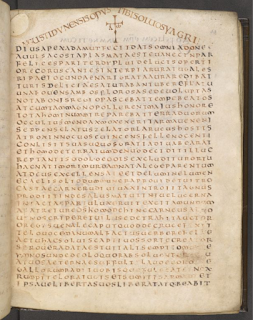

How does one describe the process of writing? At the moment, trying to overcome my fears and finish editing an article I want to publish, I would mostly reflect on its emotional challenges. Someone who has just published a book might think of what they learned along the way. Late antique authors turned to textile metaphors, using language of spinning or weaving to describe the writing process. In the mid-sixth century, the Merovingian poet Venantius Fortunatus wrote an acrostic poem for the bishop Syagrius of Autun, as a gift to accompany a plea for the bishop's help ransoming an anonymous man from captivity. At the beginning of the letter, he describes casting about for a poetic subject with a textile metaphor:

...my reading seemed to be as neglected as my practice went to waste, I found no opportunity from any subject that could be turned into poetry, and, so to speak, no fleece could be sheared to card into verse. (Venantius Fortunatus, 5.6, trans. Michael Roberts)

When a man came to the poet begging for help freeing his son from captivity (like a lot of medieval vignettes, we begin and end in media res--the poet never gives the name of father or son or his captors; nor do we know what happened next), the poet had found his subject, and determined to write something as a Thank You in Advance for the bishop's help. He settled on a poem as a suitable gift but it had to be special.

What then should my modesty offer as a gift? As I was hesitating to decide, in my inertia the words of Pindaric Horace came to mind: 'Painters and poets have always enjoyed equal sanction to dare anything.' In pondering the verse, I wondered, if each artist intermingles whatever he wants, why should not their two practices be intermingled, even if not by an artist, so that a single warp be set up, simultaneously a poem and a painting?

Accordingly when I wished to make representations for the captive in verse, bearing in mind the lifetime of the Redeemer and Christ's age when he set us free, I wove a poem of just that number of verses and letters. Consequently what was I to do or where was I to go, deterred, as I was, immediately by the difficulty of the task or rather in difficulties because inhibited by the constraints of meter and the restraints on the number of letters? By a novel calculus the limit on numbers expanded my limitations, because once a boundary was set amplitude could not give itself room nor brevity be constricted and because of the check imposed by the verses read vertically the texture allowed no free movement. For in this weave it was not possible to disrupt or slacken the threads by adding a letter lest by exceeding the number it throw the warp into disarray. And so I carefully strove that two complete verses be read at the either end, two diagonally, and one running through the middle. A further element remained, what letter I should set among them all in the very middle that would be so welcoming to everyone as to offend no one.

Accordingly, after I had computed numerically the strands of this warp, once I started to weave, the threads broke both themselves and me. I began to be bound by a task undertaken for a man to be freed, and with a reversal of roles, I enchained myself as I sought to remove the captive's ties. The difficulty of this task can be estimated from the following: if you add whenever you wish, the line grows in length; subtract, and it loses its charm; make changes and the acrostics are awry. You set a letter in place and you cannot escape it. And so when this warp was set as a trap for me in verse, so that if I escape two times I would not evade a third, like a reckless sparrow I flew through the deceptive clouds into a net, because I was caught by the wing in what I sought to avoid...

...each letter that is colored in the vertical verse both retains its place in one sequence and enters into another and, so to speak, stands as a warp and goes ahead as a weft, so that the page becomes a lettered loom. Lest we be troubled that we seem to intertwine coloured threads with the art of an Arachne, in the books of the prophet Moses, as you well know, a fine-weaving artist wove the priestly vestments. So since there is no scarlet here, the text has been woven with red. The verses, however, that run from the corners downward at an angle are stable in meaning, if inclined in stance. (Venantius Fortunatus, 5.6, trans. adapted from Michael Roberts)

|

| A ninth century manuscript of the poem. British Library, Add MS 24193, f. 30r |

As Brian Brennan notes in a recent article, this wasn't the only time Fortunatus used metaphors of weaving in his work, and his writing of ekphrasis (an exercise in classical rhetorical writing which focused on detailed description), tended to pay particular attention to lavish textiles. At the end of his four-book poem about the life of the fourth-century saint Martin of Tours, Fortunatus contrasted the quality of his writing with the worthiness of his subject in explicitly textile terms:

The thread having been unraveled is making many rucks and the disjointed fibers with their knots make a rough cloth like that carded from harsh camel hair, whereas it was fitting for Martin to be given a silken cloak with a border shining with an interweave of twisted gold thread or a toga where ran purple, intermixed with white.(Venantius Fortunatus, Life of Martin, 4.621-7, trans. Brian Brennan, lightly adapted)

There were no camels in sixth-century Gaul, so the fact that the poet assumes his audience knows what camel-hair yarn and cloth feels like is intriguing. There are two possibilities: one is that, like so many late antique authors he, his simply hearkening back to what some poet he read in school says about camel hair yarn and cloth (having knitted with yarn made in part from the hair of baby camels, I assure you that it is among the softest fibers I have ever had the pleasure of handling). And secondly, in order to make sense to their audience, poets choose relatable metaphors, so this could be a reference to an actual textile familiar to his audience.

Just a metaphor?

We tend to think of textile work as done primarily by women but the more I read about the history of spinning, weaving, knitting, lace-making, tapestry, and embroidery, the more it becomes clear that this work was not restricted by gender. (If you, too, are interested in such things, I highly recommend Piecework magazine.) Indeed, in the late Middle Ages, the great tapestry-weaving workshops were run by men, and the male professional embroiderer is not the exotic creature modern prejudices might think him. When scholars say that Fortunatus' metaphors of weaving are just literary language, they dismiss textile production as 'unofficial art from the domestic sector' (in the words of a book on late antique textiles), something divorced from the high culture of poetry.

Yet textiles and poems were closer than we might think. The weavings of the fourth-century noblewoman Sabina were the subject of a number of epigrams by her husband Ausonius:

LIII.—Lines woven in a Robe

Let the proud Orient extol its Achaemenian looms: weave in thy robes, O Greece, soft threads of gold; but let fame equally renown Ausonian Sabina who, shunning their costliness, matches their skill.

LIV.—A Second Set

Whether thou dost admire robes woven in Tyrian looms, or lovest a motto neatly traced, my mistress with her charming skill combines the twain: one hand—Sabina’s—practises these twin arts.

LV.—On the same Sabina

Some weave yarn and some weave verse: these of their verse make tribute to the Muses, those of their yarn to thee, O chaste Minerva. But I, Sabina, will not divorce mated arts, who on my own webs have inscribed my verse.

(Ausonius, Epigrams, translated by Hugh G. Evelyn White, Ausonius, Vol II (Cambridge and London, 1921). Note that in Roger Green's edition and numbering of the epigrams, these are Epigrammata 27-9.)

Aside from textile metaphors, one of the other things late antique poets appropriated was female personas--a poet writing in the voice of his wife is not unusual in late antique writing. This epigram, however, stands out as an instance were the two are combined to show a woman herself as artist and creator.

Seeking A Fine-Weaving Artist

Further Reading

Brian Brennan, 'Weaving with words: Venantius' Fortunatus' figurative acrostics on the Holy Cross' Traditio 74 (2019), 27-53

Adolfo Salvatore Cavallo, Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993). Available from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Medieval_Tapestries_in_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art [accessed 20 September 2020]

'Designing Identity: the Power of Textiles in Late Antiquity', Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, February 25-May 22 2016, Available from https://isaw.nyu.edu/exhibitions/design-identity [accessed 20 September 2020]

Michael Roberts, Venantius Fortunatus Poems (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017)

Anne Marie Stauffer, Textiles in Late Antiquity (New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995). Available from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Textiles_of_Late_Antiquity [Accessed 20 September 2020]

Jane Stevenson, Women in Latin Poetry (Oxford, 2005)