A happy and healthy New Year to you and yours! I hope you have had a joyful and wide-ranging year of reading, whatever that means in your particular circumstances.

For the past four years,

I've kept a running list of books I've finished over the course of the year. Previous lists can find found at the following links:

In 2023 I read 123 books...

Out of all of those books, there are a few that particularly stood out to me, which I would enthusiastically encourage you to check out. Part of the fun of recommending books is the connection it can create with another reader, so if you do read or listen something below and enjoy it, I'd love to hear about it!

My Recommendations

- Short Stories: "The Curfew Tolls," by Stephen Vincent Benét (which I read in 50 Great Short Stories, edited by Milton Crane); "The Girl of My Dreams" by Bernard Malamud (which I read in an edition of The Magic Barrel), "Sad, Dark Thing" by Michael Marshall Smith (which I read in Ghost, edited by Louise Welsh) at the end of which I whistled and swore softly at the perfect final twist and emotional devastation it left; "Click-Clack the Rattlebag" by Neil Gaiman (in his collection Trigger Warning); "Dinner of the Dead Alumni" by Adam Marek (another story from Ghost), which is deeply off-colour and blackly, disturbingly funny. Finally, "The Mad Lomasneys" by Frank O'Connor (I read it in The Granta Book of the Irish Short Story), with its tragicomic love story, deftly sketched characters, and impossibly perfect dialogue, is terrific fun.

- Children's and Young Adult: The Enchanted Forest Chronicles hold up to re-reading as an adult, and I loved getting to know the work of Holly Black and Leigh Bardugo.

- Romance: Alexis Hall's work does not always land for me but when they do, they really, really do. Glitterland is a gem.

- Science Fiction and Fantasy: 2023 was a standout year for my reading (and re-reading) in this genre. So many good books! Reaper Man and The Truth were a glorious introduction to Terry Pratchett. (Sharp and funny--read them both!) Ordinary Monsters is a sprawling, atmospheric Victorian fantasy. From the rereading department, the Paksworld books by Elizabeth Moon were just as diverting and delightful as I remembered them being, and Sharon Shinn's Samaria books continue to be comfort reading.

- Nonfiction: I received a copy of What an Owl Knows for Christmas, gulped it down whole, and proceeded to pepper my family with owl facts for the next five days.

- Dishonorable mention: In general, I figure that a book that wasn't to my taste will be to someone else's, live and let live. But. I so deeply, passionately disliked Lapvona by Otessa Moshfegh, that it earns my first dishonorable mention in four years of writing these posts. It's a well-crafted and totally vile book, set in a medieval fantasy world that plays up all the stereotypes of that world that scholars work so hard to replace with colour and nuance and life.

- Podcasts: You gotta listen to Alabama Astronaut, a riveting exploration of the music played in American serpent handling (signs following) churches. Really. Yes, the religion is something I (to put it politely) do not understand, but the music is electric, and the compassion and curiosity with which Abe Partridge and Ferrill Gibbs approach the people and places they come to know gives me hope for a better world.

- On the silver screen: Good Omens Season 2! Good Omens Season 2! I really can't say enough about how much I adored the second season of that show. And its beautiful, devastating ending. Broadchurch is insanely well-crafted, and Olivia Coleman and David Tennant play off each other delightfully. Diego Luna joins Coleman, Tenannt, and Toby Stephens as an actor whose craft I watch with awe and delight. Andor is incredible.

Reading

Fiction

Anthologies and Short Stories

- Parallel Hells by Leon Craig

- 50 Great Short Stories, edited by Milton Crane

- Trigger Warning: Short Fictions & Disturbances by Neil Gaiman

- The Magic Barrel by Bernard Malamud

- Ghost: 100 Stories to Read with the Lights On, edited by Louise Welsh

- The Granta Book of the Irish Short Story edited by Anne Enright

Children's Book and Young Adult

- Dark Lord of Derkholm by Diana Wynne Jones

- Year of the Griffin by Diana Wynne Jones

- The Sherwood Ring by Elizabeth Marie Pope (reread)

- Fire and Hemlock by Dianna Wynne Jones (reread)

- Searching for Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede (reread)

- Talking to Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede (reread)

- Dealing with Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede (reread)

- Calling on Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede (reread)

- Sorcery and Cecelia by Patricia C. Wrede and Caroline Stevermer (reread)

- Conrad's Fate by Diana Wynne Jones

- The Cruel Prince by Holly Black (reread)

- The Wicked King by Holly Black

- Queen of Nothing by Holly Black

- How the King of Elfhame Learned to Hate Stories by Holly Black

- Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo

- Crooked Kingdom by Leigh Bardugo

- King of Scars by Leigh Bardugo

Historical Fiction

- Prize for the Fire by Rilla Askew

Literary Fiction

- Lapvona by Otessa Moshfegh

Mystery

- The Sanctuary Sparrow by Ellis Peters

- The Raven in the Foregate by Ellis Peters

Poetry

- What it is by Esther Jansma

- The Poetry of Ennodius translated by Brett Milligan

- Frost on the window and other poems by Mary Stewart

- William Cowper: Selected Poems, edited by Nick Rhodes

- Rochester, selected by Ronald Duncan

- The Poetry of Robert Frost: The Completed Poems, edited by Edward Connery Latham

- Good Poems, edited by Garrison Keillor

Romance

- Seven Minutes in Heaven by Eloise James

- Neon Gods by Katee Robert

- Electric Idol by Katee Robert

- Wicked Beauty by Katee Robert

- Radiant Sin by Katee Robert

- For Real by Alexis Hall

- Pansies by Alexis Hall

- If Only You by Chloe Liese

- Goodbye Paradise by Sarina Bowen

- Just Like Heaven by Julia Quinn

- by Julia Quinn

- Love Theoretically by Ali Hazelwood

- An Unnatural Vice by KJ Charles

- Sorry, Bro by TaleenVoskuni

- Fumbled by Alexa Martin (reread)

- A Scot in the Dark by Sarah McLean (reread)

Science Fiction and Fantasy

- Ordinary Monsters by J.M. Miro

- Archangel by Sharon Shinn

- Jovah's Angel by Sharon Shinn

- The Alleluia Files by Sharon Shinn

- Angelica by Sharon Shinn

- Angel Seeker by Sharon Shinn

- The World We Make by N.K. Jemisin

- A River Enchanted by Rebecca Ross

- A Deadly Education by Naomi Novik

- The Last Graduate by Naomi Novik

- The Golden Enclaves by Naomi Novik

- Winter's Orbit by Everina Maxwell

- by Everina Maxwell

- Memory by Lois McMaster Bujold (reread)

- Embers of War by Gareth Powell

- Angel Mage by Garth Nix

- The Red Scholar's Wake by Aliette de Bodard

- In Acension by Martin MacInnes

- To be Taught if Fortunate by Becky Chambers

- Printer's Devil Court by Susan Hill

- The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers

- The Gospel of Loki by Joanne Harris

- Good Omens by Neil Gaiman and Terry Prachett (reread)

- Sheepfarmer's Daughter by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Divided Allegiance by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Oath of Gold by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Oath of Fealty by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Kings of the North by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Echoes of Betrayal by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Limits of Power by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Crown of Renewal by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Surrender None by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Liar's Oath by Elizabeth Moon (reread)

- Angelica by Sharon Shinn

- Angel Seeker by Sharon Shinn (reread)

- Archangel by Sharon Shinn

Nonfiction

Advice

- Overcoming social anxiety and shyness : a self-help guide to using cognitive

- How to be a person in the world: Ask Polly's guide through the paradoxes of modern life by Heather Havrilesky

Autobiography, Biography, and Memoir

- Memories by Lucy Boston

Cookbooks

- New England Open House Cookbook by Sarah Leah Chase

- The Woks of Life by Bill, Judy, Sarah, and Kaitlin Leung

- Natural by Love Food

- Summer Kitchens by Olia Hercules

- Indian Slow Cooker by Neela Paniz

- The Slow Cooker Bible by Sara Lewis, Saskia Sidey, and Libby Silberman

- I Dream of Dinner (So You Don't Have To) by Ali Slagle

Essays

- A Slip of the Keyboard by Terry Pratchett

Gardening and Nature Writing

- What an Owl Knows by Jennifer Ackerman

History

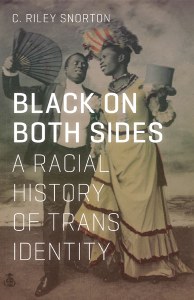

- Before We Were Trans: A New History of Gender by Kit Heyams

- The Ruin of All Witches: Life and Death in the New World by Malcom Gaskill

- The Illustrated History of Football by David Squires

- The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine by Serhii Plokhy

Travel

- A textile traveler's guide to Guatemala by Deborah Chandler

- Utrecht: Sights and secrets of Holland's smartest city by Anika Redhed

Writing

- About Writing by Gareth Powell

Viewing and Listening

Movies

- Star Wars: Episode 4 - A New Hope (1977)

- Star Wars: Episode 5 - The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

- Star Wars: Episode 6 - Return of the Jedi (1983)

- Star Wars: Episode 1 - The Phantom Menace (1999)

- Star Wars: Episode 2 - Attack of the Clones (2002)

- Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2003-2005)

- Star Wars: Episode 3 – Revenge of the Sith (2005)

- Solo: A Star Wars Story (2018) (rewatch)

- Captain America: the Winter Soldier (2014) (rewatch)

- Much Ado About Nothing (2011)

- John Wick (2014)

- John Wick: Chapter 2 (2017)

- John Wick: Chapter 3--Parabellum (2019)

- John Wick: Chapter 4 (2023)

- Mission: Impossible (1996) (watched twice, on two separate flights)

- 65 (2023)

- Die Hard (1988) (rewatch)

- Dungeons and Dragons: Honor Among Thieves (2023)

Podcasts

- Alabama Astronaut

- Ali on the Run

- Nobody Asked Us (with Des and Kara)

TV Shows

- Shadow and Bone (Season 2)

- The Expanse (Seasons 1-6)

- Bridgerton (Season 2)

- Queen Charlotte: A Bridgerton Story

- Andor (Season 1)

- Obi Wan Kenobi

- Good Omens (Season 2)

- Heartstopper (Season 2)

- Salvation (Seasons 1-partway through Season 2)

- Agents of Shield (Seasons 1- 3 ongoing)

- Loki (Seasons 1-2)

- Lost in Space (season 1 ongoing)

- Manifest (Seasons 1-3, ongoing)

- Broadchurch (Seasons 1-3)

- Foyle's War (Season 1-4, ongoing)

- Castle (Seasons 1-2, in the midst of season 3)

Youtube

- Vlogbrothers (the brothers Green)

- Run and Stretch (running warmups and cooldowns)

- Paola La (figure skating commentary)

- Full of Lit (book and TV reviews)