How does one describe the process of writing? At the moment, trying to overcome my fears and finish editing an article I want to publish, I would mostly reflect on its emotional challenges. Someone who has just published a book might think of what they learned along the way. Late antique authors turned to textile metaphors, using language of spinning or weaving to describe the writing process. In the mid-sixth century, the Merovingian poet Venantius Fortunatus wrote an acrostic poem for the bishop Syagrius of Autun, as a gift to accompany a plea for the bishop's help ransoming an anonymous man from captivity. At the beginning of the letter, he describes casting about for a poetic subject with a textile metaphor:

...my reading seemed to be as neglected as my practice went to waste, I found no opportunity from any subject that could be turned into poetry, and, so to speak, no fleece could be sheared to card into verse. (Venantius Fortunatus, 5.6, trans. Michael Roberts)

When a man came to the poet begging for help freeing his son from captivity (like a lot of medieval vignettes, we begin and end in media res--the poet never gives the name of father or son or his captors; nor do we know what happened next), the poet had found his subject, and determined to write something as a Thank You in Advance for the bishop's help. He settled on a poem as a suitable gift but it had to be special.

What then should my modesty offer as a gift? As I was hesitating to decide, in my inertia the words of Pindaric Horace came to mind: 'Painters and poets have always enjoyed equal sanction to dare anything.' In pondering the verse, I wondered, if each artist intermingles whatever he wants, why should not their two practices be intermingled, even if not by an artist, so that a single warp be set up, simultaneously a poem and a painting?

Accordingly when I wished to make representations for the captive in verse, bearing in mind the lifetime of the Redeemer and Christ's age when he set us free, I wove a poem of just that number of verses and letters. Consequently what was I to do or where was I to go, deterred, as I was, immediately by the difficulty of the task or rather in difficulties because inhibited by the constraints of meter and the restraints on the number of letters? By a novel calculus the limit on numbers expanded my limitations, because once a boundary was set amplitude could not give itself room nor brevity be constricted and because of the check imposed by the verses read vertically the texture allowed no free movement. For in this weave it was not possible to disrupt or slacken the threads by adding a letter lest by exceeding the number it throw the warp into disarray. And so I carefully strove that two complete verses be read at the either end, two diagonally, and one running through the middle. A further element remained, what letter I should set among them all in the very middle that would be so welcoming to everyone as to offend no one.

Accordingly, after I had computed numerically the strands of this warp, once I started to weave, the threads broke both themselves and me. I began to be bound by a task undertaken for a man to be freed, and with a reversal of roles, I enchained myself as I sought to remove the captive's ties. The difficulty of this task can be estimated from the following: if you add whenever you wish, the line grows in length; subtract, and it loses its charm; make changes and the acrostics are awry. You set a letter in place and you cannot escape it. And so when this warp was set as a trap for me in verse, so that if I escape two times I would not evade a third, like a reckless sparrow I flew through the deceptive clouds into a net, because I was caught by the wing in what I sought to avoid...

...each letter that is colored in the vertical verse both retains its place in one sequence and enters into another and, so to speak, stands as a warp and goes ahead as a weft, so that the page becomes a lettered loom. Lest we be troubled that we seem to intertwine coloured threads with the art of an Arachne, in the books of the prophet Moses, as you well know, a fine-weaving artist wove the priestly vestments. So since there is no scarlet here, the text has been woven with red. The verses, however, that run from the corners downward at an angle are stable in meaning, if inclined in stance. (Venantius Fortunatus, 5.6, trans. adapted from Michael Roberts)

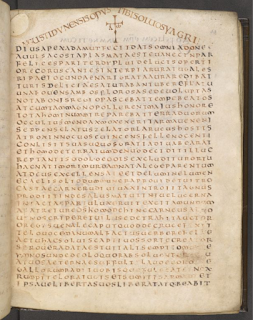

|

| A ninth century manuscript of the poem. British Library, Add MS 24193, f. 30r |

As Brian Brennan notes in a recent article, this wasn't the only time Fortunatus used metaphors of weaving in his work, and his writing of ekphrasis (an exercise in classical rhetorical writing which focused on detailed description), tended to pay particular attention to lavish textiles. At the end of his four-book poem about the life of the fourth-century saint Martin of Tours, Fortunatus contrasted the quality of his writing with the worthiness of his subject in explicitly textile terms:

The thread having been unraveled is making many rucks and the disjointed fibers with their knots make a rough cloth like that carded from harsh camel hair, whereas it was fitting for Martin to be given a silken cloak with a border shining with an interweave of twisted gold thread or a toga where ran purple, intermixed with white.(Venantius Fortunatus, Life of Martin, 4.621-7, trans. Brian Brennan, lightly adapted)

There were no camels in sixth-century Gaul, so the fact that the poet assumes his audience knows what camel-hair yarn and cloth feels like is intriguing. There are two possibilities: one is that, like so many late antique authors he, his simply hearkening back to what some poet he read in school says about camel hair yarn and cloth (having knitted with yarn made in part from the hair of baby camels, I assure you that it is among the softest fibers I have ever had the pleasure of handling). And secondly, in order to make sense to their audience, poets choose relatable metaphors, so this could be a reference to an actual textile familiar to his audience.

Just a metaphor?

We tend to think of textile work as done primarily by women but the more I read about the history of spinning, weaving, knitting, lace-making, tapestry, and embroidery, the more it becomes clear that this work was not restricted by gender. (If you, too, are interested in such things, I highly recommend Piecework magazine.) Indeed, in the late Middle Ages, the great tapestry-weaving workshops were run by men, and the male professional embroiderer is not the exotic creature modern prejudices might think him. When scholars say that Fortunatus' metaphors of weaving are just literary language, they dismiss textile production as 'unofficial art from the domestic sector' (in the words of a book on late antique textiles), something divorced from the high culture of poetry.

Yet textiles and poems were closer than we might think. The weavings of the fourth-century noblewoman Sabina were the subject of a number of epigrams by her husband Ausonius:

LIII.—Lines woven in a Robe

Let the proud Orient extol its Achaemenian looms: weave in thy robes, O Greece, soft threads of gold; but let fame equally renown Ausonian Sabina who, shunning their costliness, matches their skill.

LIV.—A Second Set

Whether thou dost admire robes woven in Tyrian looms, or lovest a motto neatly traced, my mistress with her charming skill combines the twain: one hand—Sabina’s—practises these twin arts.

LV.—On the same Sabina

Some weave yarn and some weave verse: these of their verse make tribute to the Muses, those of their yarn to thee, O chaste Minerva. But I, Sabina, will not divorce mated arts, who on my own webs have inscribed my verse.

(Ausonius, Epigrams, translated by Hugh G. Evelyn White, Ausonius, Vol II (Cambridge and London, 1921). Note that in Roger Green's edition and numbering of the epigrams, these are Epigrammata 27-9.)

Aside from textile metaphors, one of the other things late antique poets appropriated was female personas--a poet writing in the voice of his wife is not unusual in late antique writing. This epigram, however, stands out as an instance were the two are combined to show a woman herself as artist and creator.

Seeking A Fine-Weaving Artist

Further Reading

Brian Brennan, 'Weaving with words: Venantius' Fortunatus' figurative acrostics on the Holy Cross' Traditio 74 (2019), 27-53

Adolfo Salvatore Cavallo, Medieval Tapestries in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993). Available from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Medieval_Tapestries_in_The_Metropolitan_Museum_of_Art [accessed 20 September 2020]

'Designing Identity: the Power of Textiles in Late Antiquity', Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, February 25-May 22 2016, Available from https://isaw.nyu.edu/exhibitions/design-identity [accessed 20 September 2020]

Michael Roberts, Venantius Fortunatus Poems (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017)

Anne Marie Stauffer, Textiles in Late Antiquity (New York: the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995). Available from https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Textiles_of_Late_Antiquity [Accessed 20 September 2020]

Jane Stevenson, Women in Latin Poetry (Oxford, 2005)

No comments:

Post a Comment