Last year I took part in the American Historical Association's first annual summer reading challenge. While I met my goal of reading and taking notes on three books between the first of June and the end of August, I didn't finish blogging about them. Until now!

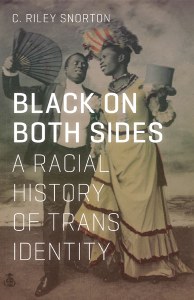

The third and final book I read for #AHAReads 2022 was C. Riley Snorton's Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity, which was inspired by the prompt to read a history of an identity group you don’t belong to.

The book blurb reads:

Black on Both Sides identifies multiple intersections between blackness and transness from the mid-nineteenth century to present-day anti-black and anti-trans legislation and violence. Drawing on a deep and varied archive of materials, Snorton attends to how slavery and the production of racialized gender provided the foundations for an understanding of gender as mutable.

|

| Cover of Black on Both Sides by C. Riley Snorton |

From the start of the book, Snorton makes it clear that he is not writing a traditional historical study.

'Organised around a series of events that provide occasion for bringing both signs--blackness and transness--into the same frame, Black on Both Sides is not a history per se as much as it is a set of political propositions, theories of history, and writerly experiments." p. 6

Non-traditional methods of analysis, he asserts, require non traditional structures (p.11-12). As a reader, I found these experiments thought-provoking and persuasive. The author's use of literary theory, trans theory, black studies, and theories of history, is that of an expert, and seeks to engage an audience able and willing to keep up. As a non-expert in any of these areas, I found it challenging, and worth it. As Snorton express it at the end of the book,

'theory, at its best, is nothing more than "dreams/myths/histories" aimed at giving expression to ways of seeing and ways of being in the world.' (p. 185)

My main takeaway from the introduction and the first chapter was that, when blackness and transness coexist, this creates the possibility of flexibility in gender. Or as Snorton puts it,

'Together this chapter and its companion, "Anatomically Speaking" (chapter 1), explore how transness became capable, that is, differently conceivable as a kind of being in the world where gender--though biologized--was not fixed but fungible, which is to say, revisable within blackness, as a condition of possibility.' p. 59

The book's five chapters are presented in three parts. The first chapter focuses on James Marion Sims' surgical experiments on enslaved black women, as way to examine how nineteenth century scientists categorised physical attributes of the body to create and support racial hierarchies. Snorton points out that, Sim's 'patients', as enslaved women, were fundamentally unable

to consent to his experimental, unanesthetized surgical procedures (p. 24), yet his discussion of how Sim's autobiographical writings, and the nineteenth century medical establishment's responses to his work, focus on the experiences and perspectives of Lucy, Betsy, and Anarcha, and the unnamed enslaved women who were his experimental subjects and unacknowledged surgical attendants. Anarcha's experiences, in particular, lead into a discussion of the relationship between odour and

disgust; Snorton raises the possibility that enslaved people may have deliberately use body odour for protection (p. 27). In discussing the limits of what we can understand about the experiences of enslaved women, Snorton uses Evelyn Hammond's work, particularly her formulation of "black holes" in our

evidence, to argue that historical analysis should be "attuned to the effects of

an undetectably present thing" (p. 43)

The chapter serves to establish our understanding of the relationship between race and gender in nineteenth century America, which builds into the second chapter, discussing the ways that free Black people, and slaves seeking freedom, used mutability of gender. While an overseas slave trade became illegal in the United States in 1808, domestic

slavery was legal until 1865, leading local and federal laws to

'articulate a grammar rife with euphemism to disavow the violent

processes by which land and persons would find primary legal expression

as property' (p. 56). One of the chapter's case studies is of the lives and writings of William and Ellen Craft. The Crafts fled enslavement in disguise--Ellen, who could pass for white, dressed in male clothing; her husband pretended to be her slave. Snorton describes the couple's different kinds of transition--between black and white, male and female, enslaved and free--as 'transubstantiation', and also explores the transformations wrought by their nineteen years of residence and activism in England, where they published an autobiography, Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom. Their book, Snorton argues, plays with audiences understandings and perceptions of racial characteristics.

'Speaking to a transnational audience of abolitioinists and others, whom he hoped to persuade to an antislavery position, Craft frames the 'cruelty' of American whiteness in terms of its particular species' characteristics.' (p. 85)

As Snorton makes clear, William and Ellen Craft's story is complex: their activism in England included support for British colonial expansion into Africa, and the educational and Christianizing projects that were part of this (p. 95).

The complexities of race and self-representation are explored in the next section, 'Transit', which contains a single chapter focused on the "female" (the quotation marks are Snorton's) in books anthologised in Three Negro Classics (1965): Up From Slavery by Booker T. Washington, The Souls of Black Folk by W.E.B Du Bois, and The Autobiography of an Ex-Coloured Man by James Weldon Johnson. Once the chapter's theoretical groundwork has been laid, Snorton's focus is on exploring the figure of the black mother. 'The black mother's gender is vestibular, a translocation marked by a capacity to reproduce beings and objects. But one should not mistake her figuration for the real.' (p. 107) The importance of keeping the differences between literary representation and reality is one that the authors Snorton examines emphasized to their audiences. As Snorton demonstrates in his analysis of the Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois explores

'how racism produces myriad institutional impediments for black artists while also undermining a myth of meritocracy, which would suggest that those black people who have been successful have done so because their work is so exceptional as to transcend race or racial prejudice...the popularity of black artists does not indicate more positive conditions for black people.' (p. 114)

These third and final section of the book, Blackout, focuses on the journalistic representations of trans stories. Snorton's methodology in engaging with the news as a source is to recognise midcentury framing and its purpose (which was to make those profiled seem like jokes), refrain from adding a 'conventionally satisfying ending' to stories that do not have one, and avoid including birth names or deadnames or accounts of trans awakenings, in favour of trying not to 'perform gender as teleology' (p. 145). The chapter focuses on reporting on the stories Black trans women, including Lucy Hicks Anderson (145-151), Georgia Black (151-157), Carlett Brown (157-161), and Ava Betty Brown (161-166), in the midcentury Black press. Reporters often reached for the story of Christine Jorgensen, a white trans woman, as a point of comparison, which in turn enables Snorton to analyse the role of race in reporting on trans stories. A key difference, as Snorton shows in the case of Ava Betty Brown, was the importance of 'black sociality'--Ava Betty Brown's friends, acquiantances and business associates all saw her as a woman, and as she said in court "If I am a man, I don't know it." (p. 162). The chapter concludes with a discussion of the story of James McHarris / Annie Lee Grant (162-174); a reporter's use of the word 'restive' sparks a thoughtful investigation of McHarris/Grant's gender fluidity. As Snorton writes,

'There is a growing consensus in transgender studies that trans embodiment is not exclusively, or even primarily, a matter of the materiality of the body. Where one locates a 'transsexual real,' whether phenomenologically, in the practices (social, legal, medical, and so on) of transition, in narrative, via the cinematic, or even in the unspeakable and unrepresentative aspects of imagining transness, shifts in relation to racial blackness. In apposition with transness, blackness, as, among modes of valuation through various forms, producing shadows that precede their constituting subjects/objects to give meaning to how gender is conceptualized, traversed, and lived.' 175

The final chapter brings together investigations of the intersection of transness and Blackness by examining reporting and film-making about the1993 murders of Brandon Teena, Philip DeVine, and Lisa Lambert. Despite the journalistic fever around Christine Jorgensen, Brandon

Teena, after his murder, was characterised in the news 'as America's first glimpse into the world of transgender people.' (178-180) In the film Boys Don't Cry (1999), and other formulations of what Snorton calls 'the Brandon archive', Philip DeVine, who was Black and disabled, is left out of the story. Snorton stresses that the chapter does not aim to add Phillip DeVine back into the story or pull

on the heartstrings. Instead, 'this chapter, following Sylvia

Winter's work, asks, What aspects of DeVine's figuration, as a matter of

sociogenesis, constitute a usable history for more liveable black and

trans lives?' (p. 183). The final section of the chapter looks at the Black Lives Matter, Trans Lives Matter, and Black Trans Lives Matter movements, and how to create a future where 'all of these lives will have mattered to everyone' (p. 198). Learning from and listening to the past, as Snorton has done in Black on Both Sides, is hopefully one step towards that future.

Further Reading

There is also further reading in the book's endnotes. Jacqueline Dowd's idea of the long Civil Rights Movement seems very important to think with; it helps 'unsettle the version of linear progression that the previous chronology implied.' (p. 233) The notes also cites Tavia Nyong'o's Essay about Caster Semenya, which links contemporary panics about Semenya's gender and athletic performance with journalistic reactions to other people with 'non-normative gender presentations', like Peter Jones; there is a later version as a journal article here.

#AHA Reads

The rest of my #AHAReads posts can be found here:

- My grand plans for the 2022 challenge

- AHA Reads #1: Theodora by Stella Duffy

- AHA Reads #2: The Dark Queens by Shelley Puhak

No comments:

Post a Comment