“I entirely agree that a historian ought to be precise in detail; but

unless you take all the characters and circumstances into account, you

are reckoning without the facts. The proportions and relations of things

are just as much facts as the things themselves.” --

Gaudy Night

“I entirely agree that a historian ought to be precise in detail; but unless you take all the characters and circumstances into account, you are reckoning without the facts. The proportions and relations of things are just as much facts as the things themselves.” -- Gaudy Night

Greetings from Oxford! My task for the first week of my project at the Bodleian has been to get to grips with the proportions and relations of the archival collections I am working with. In order to plan and prioritise my work, I have been testing my research questions to see if the information I want to find is a) present in the letters I am reading and b) takes a reasonable amount of time to collect. The answers to both questions seems to be yes so far! Because the catalogue of the Parker family letters is not very detailed, I have also set myself the task of working out how many letters there are in total. This has been less successful. It takes me a long time to count because I keep getting distracted by the contents of the letters.

The three questions I want to answer are:

- What were the Parkers' knowledge and skills, and how did they acquire these?

- Who was writing to the Parkers, and what does this tell us about the scholarly community in the early twentieth century?

- How much were they paid for their research work, and what does this tell us about the value and skill level of this labour?

So far, the range of research inquiries George, Evaline, and Angelina Parker answered seems to have been nearly limitless--everything from historical information that was pertinent to ongoing legal cases, to people researching their family trees, to academics wanting information about Bodleian materials for publications in progress, and much more. One of my favourite series of letters so far is from a French countess, Helene de Noe, who wrote to George Parker on behalf of a Franciscan priest who was preparing an edition of the works of John Duns Scottus. Not only was she deeply involved in the scholarly work of the project, but her letters contain marvelous little details of her daily life, like the time she scrawled a postscript on the back of a letter to apologise for sending Parker a late payment for his work--she'd forgotten her purse at home and didn't have time to go back and get it before the post office closed. Or the time that she wrote that she'd burned her hand and moved house, which left her scrambling to catch up on correspondence.

The letters I have been reading this week date from between 1890 and 1911, and the writing style is exquisitely formal and polite, which is great fun to read. Exceptional courtesy is especially a hallmark of letters from European researchers who chose to write in English (though the letters in French and German are delightfully courtly too.) One letter that particularly stands out was written by a pastor from Hanover, whose unique solution to his language difficulties was to compose his letter in a hodgepodge of German and English.

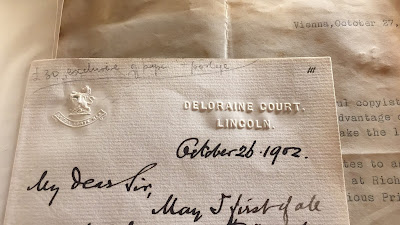

In addition to beauties of language and handwriting, some of the letters are written on extraordinarily lovely stationery. Because it has a Lincoln connection, I wanted to share an especially beautiful example.

|

| Letter from E. Mansel Sympson to Edmund Nicholson, 26 October 1902. Library Records, d. 403. Photo: Hope Williard, courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries |

The stationery is a heavy, textured, cream-coloured paper embossed with the Sympson family crest and the words Deloraine Court. Lincoln. This seems to be a Grade II listed building on James Street, in the Minster area of Lincoln; there are pictures here.

Here is a closer view of the crest:

|

| Laetus sorte mea - 'happy in my lot'. Photo: Hope Williard, courtesy of the Bodleian Libraries |

The sender of the letter was Edward Mansel Sympson (1860-1922), a Lincolnshire surgeon and antiquary. Sympson was born in Lincoln and educated at Cambridge. After getting his MD in 1890, he became a surgeon at Lincoln General Dispensary and later Lincoln County hospital. In addition to publishing on the subject of surgical discoveries, he was also a keen archaeologist, and edited the journal Lincolnshire Notes and Queries, as well as publishing books and articles on local history and architecture. His magnum opus, and the subject of this letter, was his book Lincoln: A historical and topographical account of the city, published in 1906. This letter dates from four years before, when he was deep in research. In his letter, addressed to the librarian of the Bodleian, Edward Nicholson, he writes:

October 26, 1902

My dear Sir,

May I first of all congratulate you on the recent Tercentenary of the Library? And secondly may I express my sincere thanks for the great kindness and courtesy shown to me when I was looking over the Lincoln History Ms. last month. It is again about that Ms I am writing to you...

The goes on to request that 'any competent person' made a copy of what he described as 'Lincoln History Ms (Adversaria, or notes for a history of Lincoln)', which is today Ms Gough Linc. 1; a microfilm of the manuscript can be seen in Lincolnshire archives. A member of the Parker family, possible George Parker, noted in pencil at the top of the letter that cost of the copying the full manuscript would be £30, exclusive of paper or postage.

According to the National Archives currency converter, in today's money this would be a whopping £2,357.09, and is the equivalent of three months' wages for a skilled tradesman in 1905.

Why was the copy so expensive? Most of copying of manuscripts seems to have been done by hand due to the limitations of early twentieth century photography. (It's not entirely clear to me when the Bodleian gained a specialist photograph department--particularly between 1900 and 1905, many photography jobs seem to have been passed on to Clarendon Press, whereas copying and transcription were done by the library staff or trusted independent scholars in what are called 'unofficial hours'.) While there are a number of letters which discuss or commission various types of photographic reproduction of manuscripts, most of these are followed by letters complaining that the photograph obscures or cuts off relevant details of the manuscript--and requesting that someone check the real thing in person and supply the missing information. Requests for photographs seem to become more common from around 1909 and later, and the complaints seem to be fewer, probably indicating improvements in photography techniques and technologies.

|

| The man himself! Dr E. Mansel Sympson, painted by George Henry Grenville Manton, Usher Gallery |

While the language of the letter seems to indicate that Sympson was prepared to pay for the copy whatever it cost, so far I have not found a second letter definitely indicating that the good doctor chose to have the copy made. Perhaps Sympson pursued further Lincolnshire research, in person or remotely, at the Bodleian in the years leading up to the publication of his book. I will be keeping a eye out for his beautiful stationery in the hopes of finding out!

Further Reading

E. Mansel Sympson, Lincoln A historical and topographical account of the city (London: Methuen and Co, 1906). There is a copy of this book on archive.org and in the University of Lincoln library.

"Obituary: E. Mansel Sympson, M.D., Surgeon, Lincoln County Hospital," The British Medical Journal Vol. 1, No. 3186 (Jan. 21, 1922), pp. 125-126.

No comments:

Post a Comment