This is the fourth in a series of posts about my Humfrey Wanley Fellowship project, in which I am exploring the Bodleian libraries' unofficial research department in the early twentieth century through the letters of the Parker family, found in the Library Records collection. The first post, which explains the scope and background of the project, is here; there are also posts for week 1 and week 2.

'Well,' said Harriet, 'for one thing, writers can't pick and choose until they've made money. If you've made your name for one kind of book and then switch over to another, your sales are apt to go down, and that's the brutal fact.' She paused. 'I know what you're thinking--that anybody with proper sensitive feeling would rather scrub floors for a living. But I should scrub floors very badly, and I write detective stories rather well. I don't see why proper feeling should prevent me from doing my proper job.' ~Dorothy Sayers, Gaudy Night

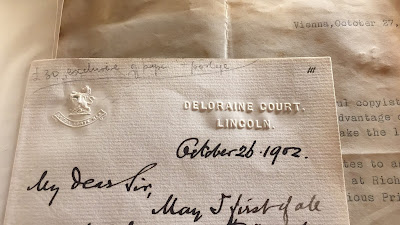

What exactly was George Parker's 'proper job'? On the surface of things, this is easy to answer: he was a senior library assistant (sometimes also described as senior assistant librarian) from 1854 until his death in 1906, an extraordinarily long tenure. But he had another job: from at least at 1896 onward, he somehow managed to fit a full schedule of answering research inquiries around his full-time work. Which did he regard as his proper job? And equally important, how did he do it all?

Part of the answer to this last question was that Parker often wasn't doing the work himself--it might be done by his wife, Angelina, a noted scholar of Oxfordshire dialect; or his daughters Angelina Frances (Annie) and Evaline. The letters they received show that the Parker family worked as a team, passing inquiries among themselves as interest or availability dictated. Additionally, those who wrote to George Parker for help knew that he might ask 'some member of your family' (in the words of a Mr Clark, who wrote on 4 August 1904), to do the copying, transcribing, translation, or reference-checking they required.

Some of these services are still ones libraries provide today: a scan and deliver service is a direct descendant of the work done by professional copyists; and some of the research support we provide is analogous to the reference-checking of the late nineteenth century. There are differences too: few librarians today would provide translation services, and while we would help readers with strategies for proof-reading and checking their references, we would not do it for them.

In the Parker's day, none of the services he and his family provided were an official part of library work, but they still had an acknowledged place within what the library thought its users might need. A fascinating library form from 1901 speaks of the 'private time' of Bodleian staff being used to answer more involved or complicated queries.

Bodleian library, Oxford

20. 4. 1901

The Librarian presents his compliments and has to express his regret that the heavy work of the library does not give its very limited staff time during official hours to comply with requests similar to yours. What you wish can, however, be done in private time at a cost of 2s 6d per hour, and you can limit the time as you like. If you wish it done, the librarian asks you to write to Mr G. Parker at the above address. You need not repeat the inquiry, as your letter will be kept.

|

| Letter from Rev. Canon Houblon, 29 April 1901, Library Records, d. 401. Photo: Hope Williard, Courtesy of Bodleian Libraries. |

|

| Library Records, f. 21. Photo: Hope Williard, Courtesy of Bodleian Libraries. |

|

| Library Records, f. 21. Photo: Hope Williard, Courtesy of Bodleian Libraries. |

Tuesday, August 3

Copying the Index to 'Aristophanes' for each copy of the Catalogue. Classified 200 slips.

Wednesday, August 4

Classified 290 slips.

Thursday, August 5

Studying the British Museum Rules of Cataloguing and Arranging titles. Classified 320 slips.

Friday, August 6

Classified 410 slips.

Saturday, August 7

and assisting Dr. Neubauer. Classified 300 slips.

Monday, August 9

and attending to Readers. Classified 380 slips.

Tuesday, August 10

and attending to Readers. Classified 250 slips.

A number of details stand out: the careful attention to the number of slips classified per day as part of a running total of slips classified during the year, and also the contrast between the details of Thursday, 5th August 1880 ('studying the British Museum Rules for Cataloging and Arranging titles') and the afterthought of 'and attending to Readers' on Monday 9 August and Tuesday 10 August. The names of people admitted to the library was recorded elsewhere; so it is perhaps not surprising that Parker's staff diary contains so little detail about who was in the library and what they were doing there. Still, the focus on cataloguing and classification versus reader services suggests the former would be more highly valued when it came time for the diary to be inspected.

Over the next few weeks I look forward to reading more about the history of the Bodleian in order to learn more about what assisting and attending to readers involved, and how this contrasted with the sort of help George Parker and his family were providing in their 'private time'. The difference between private and official hours, on the face of it a simple question, might tell a more complex story whether research work was considered to be a 'proper job' in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Further Reading

Barbara B. Moran, “E. W. B. Nicholson and the ‘Bodleian Library Staff-Kalendar.’” Libraries & the Cultural Record, 45, no. 3 (2010): 297–319. My thanks to Oliver House for recommending this fascinating article.