Like a lot of historians, I don't read history 24/7. In my pleasure reading I usually want a break from reality and one of my favourite worlds to escape into is that of the urban fantasy universe created by Patricia Briggs. Briggs is the New York Times bestselling author of over two dozen novels, including the Mercedes Thompson series, which feature werewolves, vampires, shapeshifters, and more in a contemporary western United States. The heroine of the novels, the eponymous Mercedes (Mercy) Thompson, is a biracial auto mechanic who can become a coyote, and over the course of twelve books and counting, we see her come to understand her abilities and find her place in the magical community. These books are solid comfort reading for me: I come back to them again and again because I enjoy the characters' voices and care about their problems.

That said, there's one thing about these books that has always grated on me: Mercy has an undergraduate degree in history. In my latest re-reading of the books it's been bothering me more and more.

Let's talk about why.

Mercedes Athena Thompson, BA History

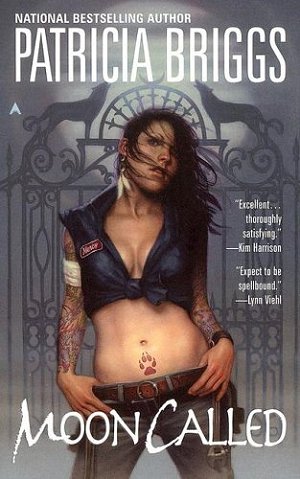

In the first book, Moon Called, Mercy introduces her history degree to the reader like this:

I have a degree in history, which is one of the reasons I'm an auto mechanic. Most of the time, I satisfy my craving for the past by reading historical novels and romances. (p. 172) My mother still blames Karen [Mercy's college roommate] for my switching my major from engineering to history--which makes her directly responsible for my current occupation, fixing old cars. My mother is probably right, but I am much happier as I am than I would have been as a mechanical engineer. (p. 212)

|

Moon Called by Patricia Briggs

|

Even after multiple rereadings, the causal connection between getting a history degree and becoming an auto mechanic throws me every time. At the beginning of the series, Mercy owns and runs a small business, an auto repair shop she bought from her former boss, a metalworking fae named Zee, after he decided to retire. She returns to the beginnings of her career a few times in the series, like so:

If it weren't for his tendency to get bored with easy stuff, he'd never

have hired me. Then I'd have had to take my liberal arts degree and

gotten a job at McDonalds or Burger King like all the rest of the history

majors. Blood Bound, p. 58

Grating, sure, but Mercy's character arc in the series is of someone finding her power and place in the world. We can dismiss this self-deprecation as the comments of someone whose confidence in themselves is somewhat shaky, right? Well, later in the series, on honeymoon with her new husband, a werewolf named Adam, Mercy is still going on about about the liberal arts to fast food pipeline:

"When we're through here, you can write to the anthropological journals

and tell them your theories," said Adam. I narrowed my eyes at him.

"Stuff that. I'll write a doctoral thesis. Then I can go do what most of

the other people with doctoral degrees in anthropology do...the same

thing that people with degrees in history do," I said. "Fix cars or

serve french fries and bad hamburgers." River Marked, p. 151

The comments about the uselessness of her history degree come up throughout the series. "I have a degree in history, so I know useless things like that" she comments when reflecting on her knowledge of the origins of the word gremlin (Blood Bound,

p. 56)--"useless" knowledge that somehow comes up again in the next

book, together with her history degree, when Mercy defends Zee, who has been charged with murder, from an expert witness hired by the police:

Ah, an attempt to discredit me. If she'd expected to fluster me, she

didn't know me very well. Any female mechanic knows how to respond to

that kind of attack. I gave her a genial smile. "I've a degree in

history and I read, Dr Altman. For instance, I know that there was no

such thing as a gremlin until Zee decided to call himself one." Iron Kissed, p. 167.

For someone who doesn't think her degree was very useful, Mercy sure thinks about it a lot. A visit of a museum on her honeymoon causes her to think back to a history professor's comments on what is preserved and why:

These weren't the kinds of baskets used on a daily basis. Most of them

were made to sell to collectors and tourists. They reminded me of a

history professor of mine who'd mourned the loss of everyday things.

Every museum, she said, had wedding dresses and christening dresses

galore, Indian ceremonial robes and beaded or elk-tooth dresses worn

only on the most special occasion. People don't save Grandma's work

dress or Grandpa's hunting leathers. River Marked, p. 129.

Things Mercy hears and sees in her daily life constantly bring to mind her history degree. In Iron Kissed,

she comments on her reaction to a song at a folk festival, "while

getting my history degree, I'd lost any romantic notions about

Bonnie Prince Charlie, whose attempt to regain the throne of England had

brought Scotland to its knees" (p. 43). In Iron Kissed, she

remember hearing Beowulf read aloud in a college class and reflects on

her knowledge of the historical roots of the English language (p. 55), on which she comments "History degrees aren't entirely useless." In River Marked, she regards her knowledge of Plato's theory of forms as use of her history degree (p. 237); in Storm Cursed we

find out that she wrote a paper on President James Monroe for a history class

(81%); she also seems to have taken classes on Nazi Germany (Frost Burned, p. 21-2; River Marked, p. 12); and knows something of the history of the Canary Islands:

I'm

a history major, so once Adam jogged my memory, I pulled up a few

random factoids--I am a magpie of history trivia. Spain had conquered

the islands that were not far off the coast of Africa over the course of

a century, just in time for them to be used as supply ports for

Columbus and most of the other Spanish explorers of the New World. I

knew a couple of other very random things. First, at the behest of the

King of Spain, Canary Islanders had settled what became San Antonio,

Texas, and set up the first official government in Texas. Second, the

original natives of the islands hadn't been of African phenotype. That

and the local island story that there was a mysterious island among the

Canaries that disappeared and reappeared had been used to fuel all sorts

of Atlantis rumors. None of what I knew appeared useful in the present

situation, so I kept my mouth shut. Night Broken, p. 190

In addition to her focus on history as facts and trivia, Mercy's degree seems to gave been focused on "people and politics [rather than] fashion and living conditions" (Silence Fallen,

28), which just sounds weird to me--in the history classes I've taken

and taught, politics and fashion are far from mutually exclusive. Mercy

seems to feel that real history is in-depth knowledge of politics. "Heck," she muses at one point in Storm Cursed where she and her werewolf pack are negotiating with the United States government, "I had a degree in history so I was supposed to be

interested in things like that, and I didn’t know who the participants

on the Joint Chiefs were" (34%).

The Mercedes Thompson series is currently twelve books long and by my count, there is only one book in the series, Silver Borne, where Mercy isn't dunking on the usefulness of history degrees or reflecting on the irrelevance of studying the past to her life and career. What does Patricia Briggs have against history majors? Is a history degree really as useless as Mercy claims?

What to do with a History Degree?

Briggs seems to have attended Montana State University to get degrees in history and German in the mid-1980s. Her first book was published in 1993, and the first book in the Mercedes Thompson series, Moon Called, was published in 2006. Interestingly, her education and start in publishing coincide with a drop-off in the number of history majors in the United States. Could the economic and social factors behind this trend be behind Mercy's comments about the usefulness of a history degree?

Or perhaps the author might be drawing on her own experiences. On her interview page, Briggs describes her employment history in between graduating from college and becoming a full time writer as 'convenience-store clerk, insurance-office gopher, substitute teacher, museum assistant and a half-dozen more'. Is this typical for history majors?

|

Patricia Briggs, History Major and NYT Bestselling Author

|

It turns out that the answer is maybe! A detailed dive into the data on career outcomes for history majors reveals that the degree is far from useless. It just isn't the case that the only result of an undergraduate degree in history will be working in fast food or as an auto mechanic: only 1.7% of history majors go into food service after graduation. As Paul B. Sturtevant (a fellow medievalist) writes in "History is Not a Useless Major: Fighting Myths With Data":

Most myths begin with a

kernel of truth that is then warped beyond recognition. The idea that a

history degree doesn’t lead directly into a profession is true only for

students who expect to become professional historians or to work in a

closely related occupation. The vast majority of history majors, of

course, do not become professional historians; according to the ACS [American Community Survey],

only 4.5 percent of history majors become educators at a postsecondary

level (that is, mostly college professors). The proportion who become

museum professionals—0.5 percent of the total—is a very small slice of

the overall pie as well.

But the ACS data imply that many history majors do not

expect to become historians and that they find meaningful careers in a

wide range of fields. A history degree provides a broad skillset that

has ensured that history majors are employed in almost every walk of

life, with some notable trends.

The notable trends Sturtevant cites include jobs in education, management and business roles, and work in the legal professions. Mercy had indeed intended to be one of those history majors who went into teaching, as her reflection on how she came to be running her business show:

He'd been working alone when I'd come needing a belt for my Rabbit

(having just blown an interview at Pasco High; they wanted a coach and I

thought they should be more concerned that their history teachers could

teach history)... Iron Kissed, p. 168.

In one of the next books, we see her catching up with a former friend about the paths their lives have taken since college:

"So you decided not to become a history teacher," Amber said as she

pulled away from the curb. Her voice was tight with nerves. The stress

was coming from her end, I thought--but then she'd never been relaxing

company. "Decided isn't quite the word," I told her. "I took a

job as a mechanic to support myself until a teaching position

opened...and one day I realized that even if someone offered me a job,

I'd rather turn a wrench." Bone Crossed, p. 112

Mercy didn't end up using her degree in the way she expected but she's still a successful (though sometimes struggling) small business owner, and she continues to enjoy engaging with the past. Throughout the series, Mercy comments on using her degree to communicate with werewolves, fae, and other long-lived magical beings. Sometimes this takes the form of educating them on what has changed between the past and the present:

I looked up at the sky and thought about how to explain twenty-first

century manners and morals to someone who had last been human before

Europeans had set foot on this continent. "Touch," I said, "is basic to

the human condition. Mothers touch their babies to bond with them. Touch

brings comfort or pain. Touch is important. The most powerful person in

a room is one who can touch anyone else--and no one can touch him back

without permission." The Romans would have substituted "sex" for

"touch", but I thought I didn't have to go that crude. Sometimes, when

dealing with very old creatures, my history degree was unexpectedly

useful. Fire Touched, p. 152

Even in everyday conversations, Mercy seems to find herself reflecting on her history degree. In Iron Kissed, she attempts to get information from a member of a local anti-fae group and gets lost in enjoyment of the chance to talk about history:

I'd started out with an agenda, but the discussion had made me forget

entirely what I was doing. Otherwise I'd have been more careful. It's

not often I got a chance to pull out my history degree and dust it off.

But still I should have realized that the discussion had meant a lot

more to him than it had to me. He thought I'd been flirting when I'd

just been enjoying myself. (p. 139)

In a later book in the series, during a chat with a well-meaning multi-level marketer from her stepdaughter's school, she wool-gathers about the past as she listens to the pitch:

The world wasn't so clear cut, I mused as she talked. There were a lot

of natural and herbal things that were deadly. Uranium occurred

naturally, for instance. White snake root was so toxic it had killed

people who drank the milk from cows who had eaten it. See? My history

degree was useful, if only as a source of material to entertain myself while listening to someone deliver a marketing speech. Fire Touched, pp. 10-11.

This statement--as you've seen, it's part of a consistent pattern throughout the series--baffles me. In book twelve, Mercy describes herself as being in her mid-thirties, and the timeline of the entire series seems to begin when she is in her early thirties--in other words, her college days were awhile ago. Why does she still feel so defensive about her degree?

Why Bother?

Mercy's history degree is evidently a big part of her identity and comes up in unexpected ways throughout the series. Readers who are less emotionally and professionally invested than me in

the value of a history degree might not react so strongly to these

comments, but as a professional historian, and someone deeply involved in the education of history majors, it pisses me off to see the degree repeatedly described as useless, especially by an author who has a history degree. Of course, it is important to distinguish the author's views from the character's--in a 2016 interview with Paul Goat Allen,

Briggs mentions her history degree, but it's not clear whether she sees

it as useful or relevant to her career as a fantasy writer.

As someone who teaches history, I would argue that history is as good a degree as any for someone who wants to be a successful writer. And furthermore, I'd like to see it represented in fiction as the valuable, vibrant field of study that it is. You don't have to be a professional historian or have studied the past beyond high school to appreciate going to a museum or historic house; to walk a heritage trail in your city or pay attention to occasions like Martin Luther King Day or Women's History Month. You don't have to have a history degree to enjoy books about the past, fiction and nonfiction alike. And yet the existence of all of these things depends on the work of history and heritage professionals, many of whom majored in history. It worries me that someone might pick up Briggs' books and take what she has to say about history degrees seriously.

Fortunately, there may be change on the horizon. The latest book in the series seems to indicate a potential shift in Mercy's attitude towards her degree and its value. In Smoke Bitten, Mercy and her pack make a betting game out of guessing the name of an amnesiac werewolf:

Being a history major, I was more than a little grumpy that no one had

told me all those stories—but I was learning. I kept the betting book,

and before I would write down the name, I made the wolf doing the

betting tell me about their candidate for the position. Maybe sometime

I’d record all the stories I learned. I couldn’t publish them since a

lot of them demonstrated just how dangerous werewolves were—and we were

currently trying to soft-pedal that for the humans we lived among so

they didn’t decide that the only good werewolf was a dead werewolf. But

still … someone should write them down. Smoke Bitten, 23%

Given all the crap Briggs has written about history majors, it's encouraging to see Mercy moving from feeling defensive and dismissive of her history degree to making opportunities to learn about the past. Will this change her attitude towards her degree? I'm curious to find out.

Soul Taken, the thirteenth book in the series, comes out in May 2022.