Three and a half years ago, when I was planning my first ever Latin classes, I stumbled upon

Dorothy Sayers' essay about her struggles with learning Latin. I am an enormous fan of Sayers' erudite and readable murder mysteries, in much the same way that I am captivated by the novels of

Dorothy Dunnett; there is something wonderful about an author who wears immense learning visibly yet lightly. Also, they're just good stories, full of the complexity of humanity.

Sayers delivered the speech 'Ignorance and Dissatisfaction' at the 1952 Summer School of the Association for the Reform of Latin Teaching; it can be found in various places on the internet now, but few people who post it acknowledge that Sayers was confessing her ignorance of Latin to an audience of Latin teachers, not the easiest crowd in front of whom to admit mistakes, then or now.

|

Dorothy L. Sayers, with friend, in Witham, Essex

|

Sayers began learning Latin at six years old, taught by her clergyman father, who had previously been a Latin teacher to the small boys ('small demons with angel-voices') at the school of Oxford Cathedral. Sayers' recapitulation of her childhood reactions to moving from memorising the declension of nouns and the conjugation of verbs into more advanced features of the language, is worth enjoying in full:

...the Active Voice, always friendly, except for a tendency to confusion between the Future Indicative and Present Subjunctive of the Third and Fourth Conjugations (the rot always seemed to set in at the Third Anything); the Passive Voice always lumbering and hostile ; the Deponents lurking meanly about, hoping to delude one into construing them as Passives; verbs like fero, so triumphantly irregular as to be permanently unforgettable ; verbs with reduplicated perfects of a giggling absurdity — peperi was always good for a hearty Victorian —and defectives, which were simply a mess. It is a nostalgic memory that I could at one time recite the whole table of irregulars without more than an occasional side-slip ; and I still remember at utor, fruor, vescor, fungor are followed by the ablative, when any more generally useful fragments of knowledge have slipped to Lethe and vanished.

By this time, of, course, the girls, the poets and the roses had upped into the background. We marched with Caesar, built walls with Balbo, and admired the conduct of Cornelia, who brought up her children diligently in order that they might be good citizens. The mighty forest of syntax opened up its glades to exploration, adorned with its three monumental trees—the sturdy Accusative and Infinitive, the graceful Ablative Absolute, and the banyan-like and proliferating Ut and the Subjunctive. Beneath their roots lurked a horrid scrubby tangle of words beginning with u, q and n, and a nasty rabbit-warren of prepositions. There was also a horrid region, beset with pitfalls and man-traps, called Oratio Obliqua, into which one never entered without a shudder, and where, starting off from a simple Accusative and Infinitive, one tripped over sprawling dependent clauses and bogged one’s self down in the consecution of tenses, till one fell over a steep precipice into a Pluperfect Subjunctive, and was seen no more.

As a young woman from a solidly middle class Victorian clerical family, Sayers had a governess and studied other languages as a child and teenager--German and French. She recounts that her growing fluency in reading and speaking these languages led her to prefer them.

To do a degree at Oxford in Modern Languages (women were only officially granted Oxford degrees from 1920 onwards, so Sayers' 1915 degree was awarded retrospectively), students of the first world war era were required to pass examinations in Greek and Latin. Sayers recounts managing to scrape through these experiences, and then starting to forget large pieces of the language in being preoccupied with other things. At the same time, though, her participation in choirs which sang medieval music left her with an awareness of

the shimmering, spell-binding magic of the mediaeval Latin

After twenty years of learning Latin, Sayers writers, she was left uncertain how to pronounce the language (having been taught multiple versions), unable to compose her own Latin prose or verse, and unable to comfortably read Latin, let alone distinguish the characteristics of different authors. And yet, she robustly defends the usefulness of Latin, for four main reasons:

- Latin Grammar teaches its students how languages work: they are consequently better able to write clearly, since English grammar is far from intuitive

- Something like half of English vocabulary has Latin roots, so someone who knows Latin has access to a wider and richer vocabulary

- Knowing Latin makes learning other Romance languages, or indeed any inflected language (that is, a language where grammatical meaning is conveyed by varying the endings of words) vastly easier; or as Sayers puts it: 'Why should a child waste time learning half-a-dozen languages from scratch, when Latin would enable him to learn them all in a fraction of the time?'

- It helps the reader make sense of allusions and Latin phrases she encounters in reading older European and English literature. (Or indeed, for the modern students, the formulas of exorcism on Supernatural, spells in the Harry Potter books, or memorial plaques in churches or public buildings...)

Sayers concludes her speech with a series of recommendations for teaching Latin in such a way as to avoid her own difficulties with the language.

Of these, the least useful is her ironclad insistence that students must begin Latin at the age of six or seven, an age where she claims they are interested in the work of memorisation that is the backbone of fluency in reading. I didn't start learning Latin until just after I turned twenty; most of my students have been at least this age if not older. While scientific research on language acquisition has only gotten clearer since Sayers' day--it is easier, faster, and of longer-term benefit to acquire multiple languages as a child--the arrow of time flies only one way.

Her suggestions for pronunciation, since this was her own insurmountable hurdle to the language, are helpful. In particular, she points to the fact that anyone who speaks a Romance language is likely to be guided in their pronunciation by the conventions of this language, and it gives the speaker something familiar to hold on to. Sayers discusses some of the practical difficulties (not very many) of English pronunciation for beginners, and suggests that the use of ecclesiastical pronunciation is the way forward.

In my own teaching, I typically default to pronouncing Latin as though it were Italian, since this is the first foreign language I learned; occasionally I am influenced by Latin I've heard sung in churches. Some of the vowels are undoubtedly wrong, but it at least means I am saying each letter or syllable that I see on the page, which I personally find helpful. I find French a bloody nightmare to read or speak, since I can never keep straight which letters I'm supposed to say and which I'm supposed to swallow, never-mind what those letters should actually sound like...! Because pronunciation can be a sticking point for some people, I encourage my students not to worry too much about saying things 'wrong'; the important thing is to get them out aloud, and then we have something to work with. As Sayers advises, consistency is the main thing to avoid confusion.

Sayers is on to something with her recommendation that students start their Latin with texts that they can read comfortably--avoiding an immediate dive into Virgil or Ovid or other authors from the time of the emperor Augustus. Firstly, these authors are way too hard, and second of all, they are far removed, culturally, from anything with which students can reasonably be expected to be familiar. Sayers' suggestion, instead, is that the rich field of medieval Latin--over fifteen hundred years of literature, mind--is a sensible starting point. For one thing, it's closer to modern languages in sentence structure and construction, and particularly for adult learners, it simply makes more sense to start with the modern form of a language and then work one's way back to its ancient versions.

Sayers advocates for speaking and writing Latin as a way to learn it. As someone who is abysmally bad at crossword puzzles and could be beaten by a dog at Scrabble, this is the sort of mental gymnastics my brain flails at. But I was made to do it as an undergraduate, and make my students do it anyway--for one thing, it humanises the language, and for another thing, it is the best way I know to make one's understanding of grammar and vocabulary absolutely ironclad. Someone can come up with the correct Latin-to-English translation without really understanding what they're doing; it simply isn't possible to do the reverse. Plus, the sense of achievement it gives is unparalleled.

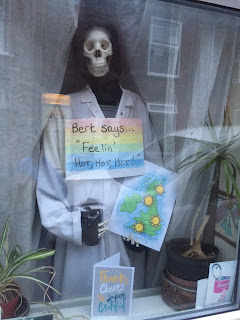

|

A side benefit of learning Latin is that once you know it, you start to see it everywhere

|

For students of Sayers' own generation, and the students of the teachers she was speaking to in 1952, language learning was a routine part of becoming an educated person. One thing I commonly hear from my students (especially British students) is that they just aren't any good at learning languages, as though one either has it the way some musicians have perfect pitch, or one doesn't, and without this gift access is forever denied. (One can see the ancestor of this thought in Sayers' speech, where she describes herself as someone with 'the gift of tongues.')

I don't like this thinking, not least because I consider myself to be in the same boat as those students. I am a native English speaker and can fumble reading or speaking five more: French, German, Italian, Latin, and Old English. And I wish I were better than I am at all of them. My issue is one that I expect actually lies at the root of many other people's insecurities about their linguistic abilities, a la this scene from Pride and Prejudice:

'My fingers,' said Elizabeth, 'do not move over this instrument in the masterly manner which I see so many women's do. They have not the same force or rapidity, and do not produce the same expression. But then I have always supposed it to be my own fault -- because I would not take the trouble of practising. It is not that I do not believe my fingers as capable as any other woman's of superior execution.'

Sayers emphasises this indirectly in her speech, although it is easy to miss since she is primarily talking about the benefits of daily individual tuition with a native speaker (the sort she got from having a French governess)--a key to language-learning is regular practice. One has to persist, even when it's confusing or boring. One of the things I address in my teaching is that a lot of students, especially ones who have never spent much time learning a language, don't know how to revise grammar or vocabulary.

I start by focusing on the value of memorisation. One thing I see with weaker students is that they insist on making sure to copy down 'the correct translation' of a sentence, so they can go away and memorise it for the exam. First of all, that memorisation energy would be much better spend on vocabulary of the sentence, and how the grammar works--this enables them to go away and read other sentences, not just regurgitate the one in front of them. Secondly, the idea that there is One True Translation is rarely if ever accurate--once one gets into translating sentences of any length or complexity, variations of the translation bring out different shades of meaning. And with really tough stuff, like the Life of Columbanus by Jonas of Bobbio or the Cosmographia of Aethicus Ister, that act of interpretation becomes an argument about what the author means and how the text works--which the reader can then take, leave, or challenge according to their own interpretation. Relying on someone else's translation as authoritative is deliberately choosing to see the world in black and white--you miss the richness of shades of colour and meaning.

There are limits to this, and especially for beginners, striking a balance between accuracy (their translation has to accurately reflect the person, number, tense, and mood of the verb or it just isn't right) and flexibility (recognising that Latin words might have several English equivalents) can be a challenge. After all, medieval people spoke and understood Latin, and an overly literal translation turns Latin into a language it's impossible to imagine real people ever speaking or writing, which leads someone already feeling like they're drowning to stop swimming. As Sayers rightly acknowledges, the right choice of reading is a

great help--students are more likely to keep doing if what

they're having to read is actually interesting.

When I was in high school, I played in the Rhode Island Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, which had occasional visits from an esteemed professional conductor, Larry Rachleff. At one point, when we were all playing something very badly, after repeated attempts to get us to play it right, he stopped us, took a deep breath, and said 'You all think I'm crazy because I care this much. I think you're all crazy because you don't.'

It's a perfect summary of what makes good teaching such a challenge--you have to think what you're doing matters, and you have to inspire other people to go along with it.

I love medieval Latin, in all its strange beauty and contradictions, and I hope that this year I will help at least a few of my students love it too.